On April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia surrendered Confederate arms and battle flags to two Michigan Regiments. Approximately 90,000 Michigan men had fought in the Civil War and 14,000 died.

Source: Michigan History

For more information, visit American Civil War-Beginning and End from Awesome Stories, including a film clip. Did you know … America’s civil war essentially started where it ended – in the backyard (and then in the parlor) of the same man, Wilmer McLean. Take a look at this piece of American (and Virginian) history.

On April 9, 1871, the most disastrous fire Alpena had seen destroyed the business district of the city. More than 100 residents were left homeless, and Alpena was left without a place for public entertainment or gatherings. A local newspaper reported on the impact of the fire: “Our city has received a severe loss, and one that it will take years to recover from.”

Source: Michigan Every Day

For a more detailed account, see History of Alpena County, pp. 234-235.

For more information about early Alpena, see The Town That Wouldn’t Die ; Alpena, Michigan By Robert E. Haltiner

Perhaps no other area of Detroit has changed more often and more drastically over the years than Campus Martius, the city center. Over the years, Old City Hall, the Majestic Building, the Pontchartrain Hotel, the Family Theatre, the Hammond Building and the old Detroit Opera House have all come and gone.

Only one landmark has outlived them all.

The Soldiers and Sailors Monument is among Detroit’s oldest pieces of public art and was one of the first monuments to honor Civil War veterans in the United States. It was announced by Gov. Austin Blair in 1865 that money would be collected to erect a tribute to Michigan’s soldiers killed in battle. Detroit, being the largest city, won the right to the monument.

The cornerstone for the monument was laid July 4, 1867, but not in Campus Martius, where the monument stands today: The original plan was to put it in the eastern half of Grand Circus Park. The previous year, the City Council granted permission to the Soldiers Monument Association to build the monument in either Campus Martius or East Grand Circus Park. After much debate, the latter was picked. Before the end of 1867, the argument over the site was renewed, leading the council to vote again, this time opting to relocate it in the center of Woodward Avenue between the halves of Grand Circus Park — also to much dismay. Finally, a special committee of the council resolved in September 1871 that the best place for the monument was the open square in front of City Hall.

The bronze and granite sculpture was formally unveiled on April 9, 1872, though some of its statues were not added until July 18, 1881. Among the military commanders of Civil War fame attending the ceremony were Gens. George Armstrong Custer, Ambrose Burnside, Philip Sheridan, Thomas J. Wood and John Cook. The estimates were that 25,000 visitors turned out for the event, and each of the state’s main cities was represented by a marching delegation. Detroit’s hotels could not accommodate the crowd and some people had to sleep on the floors of the halls and parlors of taverns.

The Classical Revival monument stands more than 60 feet tall and cost more than $75,000 ($1.3 million today) to build. It was sculpted by Randolph Rogers, an Ann Arbor native who studied at the Academy of St. Mark in Florence, Italy, under Lorenzo Bartolini. Rogers won the commission after a public competition in 1867. He also is known for the bronze doors for the U.S. Capitol’s main entrance and created monuments like the Sailors and Soldiers in other cities. For this commission, Rogers modeled the sculptures in Rome and had the bronze cast in Munich, Germany.

Its body is made of Rhode Island granite; its figures are cast of bronze and rest on octagonal tiers. The bottom has four screeching eagles with outstretched wings, symbolizing America and freedom. Above that are four 900-pound statues that represent the four U.S. branches of the military: infantry, artillery, cavalry and the Marines. Behind them are bronze medallions of Civil War union leaders President Abraham Lincoln, Gen. U.S. Grant, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and Adm. David Farragut. The next tier has four allegorical figures representing Victory, Union, History and Emancipation.

Topping off the monument is a 3,800-pound personification of a victorious Michigan as an Indian queen in a winged helmet, brandishing a sword in her right hand and a shield in her left. She depicts Michigan as being strong, proud and brave. The personification of Michigan is similar, though more aggressive, than the one on the Russell A. Alger Memorial Fountain in Grand Circus Park.

Below the Indian queen is an inscription that reads:

“Erected by the people of Michigan in honor of the martyrs who fell and the heroes who fought in defence of liberty and union.”

One of the figures on the monument is of a black woman, representing Emancipation. She crowns the soldiers and sailors with wreaths, representing gratitude for emancipation and is said to have been inspired by Sojourner Truth. But there is no recognition of this in the account of the unveiling of the monument, nor in Lorado Taft’s comment on the monument in his history of American sculpture.

The structure was added to the state register of historic sites Feb. 17, 1965. It joined the National Register of Historic Places on May 31, 1984.

For the full article, see Dan Austin, “Soldiers and Sailors Monument“, HistoricDetroit.org, 2018

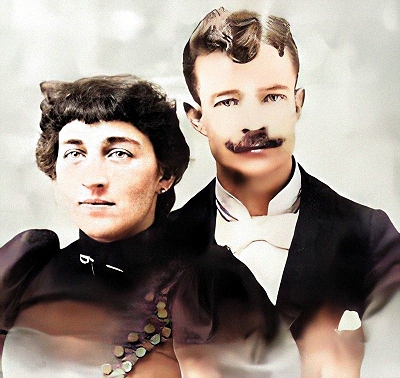

Hugo (Hughie) Cannon was born in Detroit, Michigan, to actors John S. Cannon and May Brown on April 9, 1877, some seven months after their Illinois marriage.

Beginning around 1901, Cannon’s story was closely tied with Jackson, Michigan, about 80 miles due west of downtown Detroit. There he quickly gained a reputation as a likable and stellar ragtime pianist. Jackson was considered to be a rather rough railroad town, and was sometimes referred to as “Little Chicago.” The Michigan Central Railroad kept one of their major satellite repair shops there, and an average of 3,000 railroad employees either lived or lodged around Jackson at any one time. The 1900 City Directory lists 75 saloons around the downtown area, so there were plenty of opportunities for Hughie to play, and to drink his wages.

|

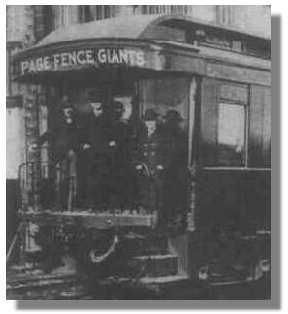

Before the creation of the first Negro National League (NNL) in 1920, many professional and semi-professional African American teams took to the ball field, giving hundreds of men the chance to earn their livelihood by playing baseball. One of the best of these clubs, the Page Fence Giants, found a home in Adrian, Michigan, not far from Detroit, in 1895. Made up of crack players, including some of the biggest stars of the day, the Giants took part in a number of memorable games — most of them resounding victories for Page Fence — on their way to a self-proclaimed colored championship.

In 1894, The Local Light Guard Armory in Adrian worked hard to put a solid nine on the baseball diamond. Under manager L. A. Brown and team president Rolla Taylor, the Light Guard club came together to give the Adrian fans something to cheer about as a mix of veterans, like veteran catcher Henry Yalk, and newcomers, including soon to-be ace George Wilson, brought baseball to the city. Wilson, from Palmyra, Michigan, was only 17 years old, but he would lead the team to victory after victory, pitching with a confidence and maturity beyond his years. His first win, in late July 1894, was a 12-2 victory over nearby Hudson, Michigan’s nine was a preview of things to come.

Against a strong contingent from Findlay, Ohio, the Light Guard Armory team fared less well, losing 19-9 and 6-0. But the series would eventually be counted a success, as it brought them into direct contact with Findlay’s star second baseman, Bud Fowler. Fowler had helped his club beat the Detroit Tigers twice, and in the process had gained a national reputation. Announcing plans to relocate to Adrian in 1895, joining former teammate Doug Underwood, Fowler told local reporters that his new Cuban Giants team would play at Lawrence Park, after some necessary repairs were made. Fowler wanted to have his team play in Findlay, he said, but was not able to secure the needed backing for the team.

Local sports promoter Len Hoch saw Fowler’s plan as a great way to talk up the small town of Adrian. Hoch agreed to put up part of the $500 needed to finance the new ball club. Both Hoch and Fowler wanted to develop a team that had a national reputation, which meant the team would need to travel a great deal. To accomplish their travel Fowler wanted the team to have its own railroad car. Additionally, for the club to be a success, on and off the field, Fowler believed pitcher George Wilson would be a central cog. The other key would be attracting future Hall of Famer Grant Johnson to Adrian from Findlay.

On September 20, 1894, the local papers announced, “Bud Fowler’s scheme has finally materialized.” The Page Woven Wire Fence Company saw this new venture as a great advertising opportunity for their fences and became the team’s primary sponsor. They put their name on the railroad car the team traveled in and their initals on the jerseys of the club’s black and maroon uniforms. In addition to securing a sponsor, Fowler succeeded in persuading Johnson and Wilson to join this new club. The team would go on to barnstorm around the midwest.

According to wikipedia, the team played it’s first game on April 9, 1895.

n May 1895, the Page Fence Giants rolled into Kalamazoo for the first time to begin a best-of-three series against the state league Kazoos at the North Street ballpark, and true to form, they beat the local team rather badly in the process. “The [third] game was a hot one from the start,” stated a reporter for the Telegraph, “and although it went deservedly to the hard hitting visitors, it was by all odds the prettiest one put up here this season.”

“Nine chocolate colored ball players, traveling under the name of the Page Fence Giants, in a private car, have been making a tour of the central states, demonstrating to the Western, National and minor league ball players that the latter knew nothing of how the game should be played. St. Paul, Cincinnati, Grand Rapids, Dubuque and others had succumbed to African muscle and brains, and yesterday Kalamazoo’s scalp was added to the already big stock of cappilaceous relics… (the Giants) rubbed the rich celery earth of the league grounds deep into the hides of the local players…” —Kalamazoo Daily Telegraph, 16 May 1895

To help generate crowds when they arrived in a city, the players dressed in their railroad car and then paraded to the ball field riding on 12 monarch bicycles purchased from William S. Sheldon, owner of the Monarch Bicycle Company, another of the team’s sponsors, while fans followed them to the ball diamond. The Giants traveled in style. Their 60-foot car had sleeping areas as well as their own porter and cook so as to avoid the hassles of having nowhere to sleep or eat on the road in Jim Crow America. Fowler believed this was necessary since they had no home ball park (Lawrence Park, in Adrian, was also used by the Demons, also known as the Reformers, in 1895) and consequently spent most of their time on the road.

As was so often the case with early black teams, even when successful on the field, the Page Fence club ran into financial difficulties, leading them to reorganize in 1899, when they began the season as the Columbia Giants, sponsored by the Columbia Club of Chicago. They found themselves playing an early game in Racine, Illinois, where they picked up a new player named John Brown. Despite the reorganization, local papers continued to refer to the barnstorming team as “Page Fence” or as the “former Page Fence Giants,” no doubt believing their readers were familiar with the team and its reputation for strong play As late as 1903, in fact, after the Page Fence Giants had been gone for five seasons, some papers still referenced the early championship squad.

One of the premier professional colored teams in the 1890s, and the first to appear in the Midwest, the Page Fence Giants demonstrated early that black baseball could succeed outside of the East Coast, where teams such as the Cuban Giants and X-Giants had flourished in part because of the large fan bases found in cities along the seaboard. While there are still many gaps in the record of the Giants, the skeletal record provided in this article supports their claim to be the champions of black baseball in 1895 and 1896. Beating both the Chicago Unions and the Cuban X-Giants in head-to-head series, taking games against Western Association and Western League clubs, and trouncing many of the smaller, unaffiliated teams of the East and West, Page Fence dominated the competition and, barnstorming their way across multiple states, expanded the footprint of black baseball.

Sources:

Lelie Heaphy, “The Page Fence Giants: Nineteenth Century Champions. Black Ball 5.1 (Spring 2012): 76-83.

Page_Fence_Giants wikipedia entry

Page Fence Giants 1894-1898, courtesy of the Negro League Baseball Players Association.

Richard Bak, “Giants of Adrian may have been best baseball team in Michigan in the 1890s”, Detroit Athletic Club, February 11, 2012.

Baseball in Kalamazoo: Black Teams – Kalamazoo’s Early African American Baseball Teams, courtesy of the Kalamazoo Public Library.

The Page Fence Giants : a history of Black baseball’s pioneering champions / Mitch Lutzke. Jefferson, North Carolina : McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2018.

According to the Warren-Cramlon Law of 1909, no city should have more than 1 bar per 500 residents. According to the latest census, Detroit should have no more than 1000 bar rooms, but in fact has 1550 bar licenses. And there is no indication the number will go down since there have already been more applications this year than in 1911.

REDUCE THE SALOON NUMBERS HERE. Detroit Free Press, April 9, 1912.

BAD BARS TO CEASE EXISTENCE: HERMAN WARTELL’S “ANNEX” AND SIMILAR NOTORIOUS SALOONS WILL BE PUT OUT OF BUSINESS BY COUNCIL COMMITTEE. REFUSE LICENSE NO MATTER WHO ASKS ALDERMEN DETERMINED TO EXCLUDE PLACES OF EVIL REPUTATION, DESPITE CHANGES OF NAME, OF OSTENSIBLE APPLICANTS. Detroit Free Press, April 9, 1912.

Other news from the Detroit Free Press, April 9, 1912:

WOMEN TALK TOO MUCH: BOSTON DOCTOR SAYS CHATTER MAKES THE DEARS NERVOUS.

GIRL’S PARENTS FOIL ELOPERS: INDIANAPOLIS SWEET 16 AND U. OF M. GRADUATE TRIPPED ON LICENSE AT ST. JOSEPH.

TAKES HAIR TONIC FOR COLD: (ASSISTANT PROSECUTOR) “WILLIE” HESTON SWALLOWS RESTORER BY MISTAKE; GOES HOME ILL!.

Note : The Main Library now provides the MSU community online access to the historical Detroit Free Press from 1858 through 1922.

On April 9, 1948, Michigan State College President John Hannah announced that no groups or individuals on the campus are admitting that they are Communists. Hannah and S. E. Crowe, dean of students, were subpoenaed by state Sen. Matt Callahan (R-Detroit) to appear before his Michigan Senate Un-American Activities Committee, which conducted its meetings behind locked doors, and only allowed a few reporters to attend. (The Michigan Attorney General was barred.)

Hannah stated communists could not be barred from enrolling because MSC does not ask political affiliations on applications for enrollment. Since the state of Michigan recognizes communist candidates on its election ballots, MSC is not going to ban any such group, but since a group would have to get faculty sponsorship, it was unlikely any such group would ever form.

Crowe said the Spartan Citizens League, formed a year ago when the American Youth for Democracy was banned on campus, contained some “liberal thinkers.” As far as college authorities are able to determine, he, said, the meetings are mostly concerned with “long hair” art, music and literature.

Sources:

MIRS News Service.

“Official Says MSC Has No Known Reds”, Detroit Free Press, April 10, 1948, p.4.

Owen C. Deatrick, “No Danger of Red Groups Starting at MSU, Hannah Says”, Detroit Free Press, April 13, 1948, p. 14.

The Red Wings closed out its 38-year residency at Joe Louis Arena with a 4-1 victory over the New Jersey Devils in front of 20,027 raucous fans, who hurled a reported 35 octopuses on the ice during the game – a unique Red Wings tradition that dates to the early 1950s.

For the full article, see Bill Shea, “Red Wings, under a flurry of octopuses, bid farewell to Joe Louis Arena with 4-1 win over Devils“, Crain’s Detroit Business, April 9, 2017.

Dan Holmes, “19 Reasons We’ll Always Remember The Joe“, Detroit Athletic Company Blog, April 8, 2017.

While in the House of Representatives, Anderson concentrated on public welfare issues and chaired the Industrial Home for Girls Committee. She was particularly interested in public health issues, especially the fight against alcoholism and tuberculosis. Prior to her term, she had organized the first public health service in Baraga County and was instrumental in securing the county’s first public health nurse. She also became actively involved in the Michigan Grange and served as the Upper Peninsula officer.

Anderson was educated as a teacher at the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas, which is known today as the Haskell Indian Nations University. She taught school in the Upper Peninsula for several years. At a time when minorities, including Native Americans, were subjected to considerable economic and social discrimination, Anderson’s determination to attend college and return the benefits of her education to her community was notable. Her role as educator, legislator, and public health reform leader aided the Native American community as well as the whole of society.

Both the Anderson House Office Building in downtown Lansing and the recently opened Cora’s Cafe inside are named after her.

Sources :

Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.

Rep. Dianda Honors Cora Anderson, Michigan’s First Female State Rep, Michigan House Democrats Blog, December 8, 2016.

“Women’s History Month: Cora Anderson, first in state house”, Lansing State Journal, March 23, 2014.

Photo source : Michigan Historical Review Facebook Page, April 10, 2017.

Detroit, April 10-15, 1882

Elsa Von Blumen Aboard a Highwheeler. Sometimes called a “Bone Shaker”, “Velocipede”, “Penny Farthing”, and “Ordinary”.

In the late 1870s women’s bicycle racing was developing into a popular spectator sport. The first exhibitions and/or races were held in France, but soon spread to the United States and then England. Though some denounced the ladies as common showgirls, they were in fact highly trained and motivated athletes. The press covered many of these events and helped make the female riders stars of the cycling world. And the ladies were willing to compete in whatever fashion that guaranteed publicity and/or prize money, whether it be against themselves, male cyclists, pedestrians, or even trotting horses.

In such a vein, Ms. Elsa Von Blumen (a pseudonym for Caroline Kiner) visited Detroit in April 1882 for an exhibition, promising to ride 1,000 miles in six days, something she’d accomplished in Pittsburgh back in December. A custom velodrome (bicycle track) — perhaps the first in Detroit — was built inside the former Music Hall for the occasion.

More About Van Blumen

According to the Auburn Bulletin, Tuesday, February 22, 1887, recycling an article from the Oswego Palladium, “Von Blumen was born in Pensacola, Florida, October 8, 1859 and moved to Albany, N.Y., in the following year. Her maiden name was Carrie Kiner. In 1865 she lived in Oswego. The cold winters, common to all cities upon the great chain of lakes, proved too severe for her delicate frame. She rapidly declined, and was pronounced by several physicians to be in the first stages of consumption. By the advice of friends, she undertook a course in physical exercise, often walking five or six miles a day, together with light exercise with dumb-bells and clubs. The beautiful results were soon manifest. She became possessed of extraordinary powers of endurance, and showed herself capable of undergoing prolonged exertion without injury. About six years ago she moved with her mother and sisters to Rochester, where she has since resided at No.75 Munroe avenue.” For a short time, she was married, but the brief experience did not end happily and she soon returned to bicycle racing as a pursuit.

Von Blumen first made a name for herself as a pedestrian racer, which was also a popular sport at that time. There were plenty of endurance walking races, including six-day races in places like Madison Square Gardens and even Detroit. While endurance racing was challenging, she eventually switched to highwheeler bicycle racing to help support her mother and younger sisters with prize money and appearance fees.

On one such occasion, on May 24, 1881, about 2,500 people gathered at Rochester’s Driving Park to watch the 21-year-old Von Blumen take on a race horse named Hattie R. They cheered as she beat the horse in two out of three heats.

Elsa Von Blumen racing Hattie R from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.

Sue Macy, author of the book “Wheels of Change” says she was “one of the first competitive female athletes in the United States” — a role model for girls and young women at the start of the suffrage movement.

She told Bicycling World in 1881, “I feel I am not only offering the most novel and fascinating entertainment now before the people, but am demonstrating the great need of American young ladies, especially, of physical culture and bodily exercise. Success in life depends as much upon a vigorous and healthy body as upon a clear and active mind.”

Her Detroit Endurance Event

Her visit to Detroit in 1882 didn’t start out well. She contracted a mild form of smallpox (called varioloid) shortly after arriving and was confined to the “pest house.” The case was very light and she soon recovered according to city’s Board of Health report.

To promote her race, images of her were posted at store shops around town. She offered a special invitation to other women.

Her plan was to ride for 91 hours at 11 miles an hour on a track that was 15 laps to a mile. The track was surveyed by the Assistant City Surveyor for accuracy. Chairs were arranged inside the track for spectators. There was a band to play music whenever she rode.

The Free Press downplayed her chances simply based on her appearance, “115 pounds, apparently not possessed of any of the physical characteristics essential to the successful accomplishment.”

She began her Detroit ride on Monday, April 10th, 1882 at 1 AM wearing a steel-gray suit trimmed with bullion fringe. She bowed to the crowd, got on her silver highwheeler bike, and the band started to play. She rode 35 miles in 3 hours before stopping for a two-hour sleep break. At the end of the first day, she’d ridden 140.

She mostly lived out of a Music Hall dressing room, ate three regular meals along with beef tea with crackers and some sips of port wine.

On Tuesday, she rode nearly 60 miles in the morning. Mr. Snow from the Detroit Bicycle Club rode with her for nine miles and crashed “in fine style” per the Free Press. The event manager also offered any local bicyclist $100 if they could match her miles for the final four days. She rode another 100 miles before the day was over.

Wednesday saw a slower pace at just over 10 MPH. Local ride “Robinson” was on the track riding behind her and hoping to win the $100 challenge. She finished the day with just over 449 miles.

Von Blumen continued on Thursday with another 70 miles by 3pm. The Free Press reported her looking “pan and wan, but as determined as ever.” She confidently stated that she would finish, but her nurse did mention her feet were getting cold. They had resorted to using a battery (!) to restore the blood circulation. She ended the day with 583 miles.

Because of the highwheeler’s design, taking a “header” was always a possibility.

Because of the highwheeler’s design, taking a “header” was always a possibility.

Friday’s low moment occurred when a spectator stepped on the track and caused her to crash over the bars. She was thrown up against the steam heaters, hurting her head, and bruising her right leg from hip to ankle. She was carried to her dressing room and everyone thought she was quitting. Not so. She was back on her bike in 30 minutes, dizzy, weak and riding slow. While she ended the day with 707 miles, Robinson was now 7.3 miles ahead of her.

She started riding on Saturday still sore from the previous day’s crash yet got in 46 miles by noon. Her pace quickened. She had 800 miles by her dinner break. Many Detroiters began filling the Hall to watch, but especially women.

At 11:58 PM she got in 850 miles and the crowd burst into enthusiastic applause. As she stopped, so did the orchestra It was an impressive endurance feat, but especially given her illness before the event began.

Robinson did out ride Von Blumen over the four days by just thirteen miles, earning himself the $100 prize.

Financial Troubles

Although the event drew a fair number of paying spectators, it still lost $400. To help pay off her debt, Detroit citizens arranged a benefit race at Recreation Park. Von Blumen would race in a 5-mile time trial event and two 5-mile races against some horses. The Detroit Bicycle Club would also hold races for its members. There was a 25 cents admission.

But before the event took place, her doctor during the 1,000 mile attempt claimed he was owed $121 dollars and the police seized her bicycle.

Fortunately a sympathetic officer let her ride her bicycle and she beat both of the horses before a good number of onlookers.

Another benefit was held a week later where Von Blumen rode a 7.5 miles race against three horse relay team doing 15. She won by a mile, literally.

It appears she departed Detroit for Grand Rapids during the couple weeks that followed and probably stopped at other locations to race as well. In 1886, she rode 367 miles in 51 hours in a race at Rochester’s Convention Hall against a pair of men. They took turns riding, but she beat them without needing a partner. She continued bicycle racing until highwheeler bicycling went out of style.

A sketch of Elsa Von Blumen with her high-wheeler bicycle from 1885 courtesy of the Rochester (NY) Public Library, Local History & Genealogy Division

It doesn’t appear she came back to Detroit, but she certainly left her mark. There’s little doubt her event inspired many Detroit women and girls to take up bicycling, but especially after the safety bicycle became popular in the 1890s.

Elsa von Blumen on a safety bicycle from Wheels of Change by Sue Macy.

Early Detroit Bicycle Shop showing both highwheelers and safety bicycles (Detroit News).

In 1896 Susan B. Anthony noted that “the bicycle has done more for the emancipation of women than anything else in the world.” The bicycle craze helped kill the bustle and the corset, and instituted “common-sense dressing” for women and increased their mobility considerably.

Sources :

Sue Macey, “Elsa Von Blumen & Detroit’s first indoor bicycle track”, m-bike.org , January 26, 2018.

Further Reading: An interesting interview with Elsa Von Blumen about a “very funny incident.” It was published on the front page of the Detroit Free Press on April 28, 1882.

A Vintage Ride entry from the Webster Museum

Caroline Wilhelmina “Elsa Von Blumen” Kiner Roosevelt (1859-1935) entry from Find a Grave.

Mike Fishpool, “Lady Racers: The Origins of Women’s Cycle Racing“, Playing Pasts, June 25, 2018

Wheels of change : how women rode the bicycle to freedom (with a few flat tires along the way) / Sue Macy. Washington, D.C. : National Geographic, [2011] Take a lively look at women’s history from aboard a bicycle, which granted females the freedom of mobility and helped empower women’s liberation. Through vintage photographs, advertisements, cartoons, and songs, Wheels of Change transports young readers to bygone eras to see how women used the bicycle to improve their lives. Witty in tone and scrapbook-like in presentation, the book deftly covers early (and comical) objections, influence on fashion, and impact on social change inspired by the bicycle, which, according to Susan B. Anthony, “has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.”

Bicycle : the history / David V. Herlihy. New Haven : Yale University Press, [2004] During the nineteenth century, the bicycle evoked an exciting new world in which even a poor person could travel afar and at will. But was the “mechanical horse” truly destined to usher in a new era of road travel or would it remain merely a plaything for dandies and schoolboys? In Bicycle: The History (named by Outside magazine as the #1 book on bicycles), David Herlihy recounts the saga of this far-reaching invention and the passions it aroused. The pioneer racer James Moore insisted the bicycle would become “as common as umbrellas.” Mark Twain was more skeptical, enjoining his readers to “get a bicycle. You will not regret it–if you live.” Because we live in an age of cross-country bicycle racing and high-tech mountain bikes, we may overlook the decades of development and ingenuity that transformed the basic concept of human-powered transportation into a marvel of engineering. This lively and engrossing history retraces the extraordinary story of the bicycle–a history of disputed patents, brilliant inventions, and missed opportunities. Herlihy shows us why the bicycle captured the public’s imagination and the myriad ways in which it reshaped our world.