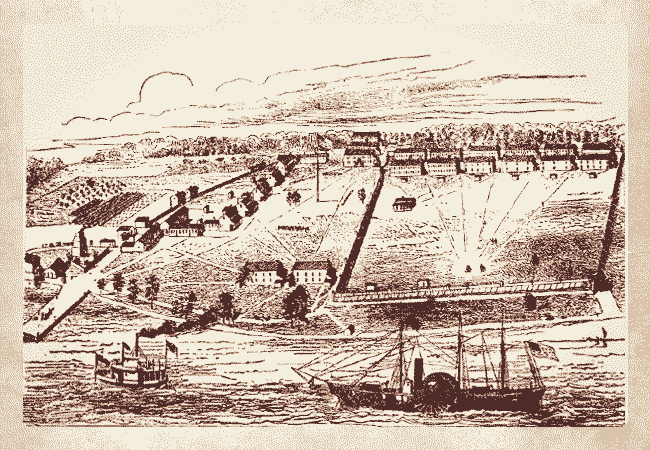

The above illustration of Johnson’s Island was made by Edward Gould, Company B, 128th Ohio during the war. In the foreground is the U.S.S. Michigan. On the left is the fort’s wharf with a road leading back to the troops quarters and on to where the artillery position was created in 1864. Inside the stockade you can see the 12 2-story block houses that housed the prisoners. Each block house was responsible for its own mess. Behind the last row of block houses were the latrines or what they called their “sinks”. The radiating lines running from the block houses to the center are paths leading to pumps that were used to pump water from the bay into wells used by the prisoners.

No Civil War battles were fought on Michigan soil, but many Great Lakes mariners and ships fought for the Union Cause. It took the Union prison at Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie near Sandusky to bring the Civil War directly to the front doorstep of Ecorse, Michigan, a small village on the Detroit River. Confederates had tried numerous times to escape from the prison at Johnson’s Island, but the record shows only a few successful escapes before 1864. The year 1864 proved to be a successful year for escapes.

The Sandusky Register reported the escape of six rebel prisoners on January 4, 1864. The Register said that six Confederates – Major Stokes, Captain Stokes, Captain Robinson, and Captain Davis, all Virginians, Captain McConnell of Kentucky and Major Winston of North Carolina made a crude ladder by tying the legs of a bench with a clotheslines across a board at spaces of about three feet, about four feet short of the desired length. They gathered as much civilian clothes as they could from friends in the prison.

Some of the prisoners made it as far as Trenton, Michigan, before crossing the ice to freedom in Ontario. They eventually traveled up the St. Lawrence River to the ocean and Bermuda. Then they sailed on the blockade runner Advance to North Carolina and home.

Source : Kathy Warnes, “Six Confederate Officers Stage a Nautical Escape Through Downriver”, Definitely Downriver, October 2012.

The USS Michigan was laid down in December 1906; the hull was launched May 26, 1908; but the USS Michigan was not commissioned for active duty until January 4, 1910.

The Michigan and its sister ship South Carolina were both assigned to the Atlantic Fleet and were the US Navy’s first class of dreadnoughts.

USS Michigan, a 16,000-ton South Carolina class battleship built at Camden, New Jersey, was commissioned on January 4, 1910, one of the first “battlewagons” built by the U.S. Navy. After initial operations along the Atlantic coast and in the Caribbean, she steamed across the ocean to visit England and France during November and December 1910. Michigan spent the next eight years taking part in regular Atlantic fleet exercises and cruises off the eastern seaboard, in the Caribbean and off Central America. In April-June 1914, she played a major role in the Vera Cruz incident, with many of her men serving ashore. The battleship suffered two notable accidents, one in September 1916 when a twelve-inch gun of her second turret burst while being fired and the second in January 1918 when her “cage” foremast collapsed during a storm at sea.

Michigan’s First World War operations included convoy, training and battle practice operations in the western Atlantic area. In January-April 1919, soon after the war’s end, she was employed as a troop transport, bringing home over a thousand veterans of the conflict. In mid-1919, Michigan passed through the Panama Canal to the Pacific on a midshipmen’s training cruise that took her as far west as Honolulu. When the Navy formally adopted ship hull numbers in 1920, she was designated BB-27. Michigan made another long-distance training voyage in mid-1921, this time calling on European ports from Norway to Gibraltar. She was decommissioned in February 1922. Made redundant by the Washington naval limitations treaty, USS Michigan was stricken from the Navy list in November 1923 and scrapped during 1924.

Sources:

Mich-Again’s Day.

On January 4, 1918, production began at the historic Ford River Rouge plant.

At the height of production in the 1930s, more than 100,000 people clocked in at “The Rouge” regularly. Operating such a massive production complex required intricate coordination and planning. Besides assembly lines for building automobiles, the complex also included a massive power plant, 100 miles of railroad track and its own police and fire departments.

The Rouge is now called the Ford Rouge Center. The 600-acre site remains Ford Motor Co.’s largest single industrial complex. Now under revitalization, the complex will include one of the world’s most advanced and flexible manufacturing facilities, capable of building up to nine different models on three vehicle platforms. The Dearborn Truck Plant will become the centerpiece of the new Ford Rouge Center, the largest industrial redevelopment project in U.S. history and the flagship of Ford’s vision of sustainable manufacturing for the future.

Henry Ford’s plan in creating the Rouge was to attain complete self-sufficiency by owning, operating and coordinating all the resources needed for automotive production. At the time, Michigan was ideally suited for automotive production because many of the raw materials needed were located within Michigan, including forests, iron mines and limestone quarries. Ford also owned coal mines in Kentucky, West Virginia and Pennsylvania, and a rubber plantation in Brazil.

Ford’s vision was never fully realized, as bringing all aspects of auto production under one roof — or at least within one complex — proved too unwieldy. Still, no other auto manufacturer came as close.

Ford’s massive production complex is located a few miles south of Detroit at the confluence of the Rouge and Detroit rivers. Originally, the Rouge was 1.5 miles wide and more than a mile long. The plant encompassed 93 buildings totaling more than 15.7 million square feet of floor space served by a network of 120 miles of conveyors. Equipment included ore docks, steel furnaces, coke ovens, rolling mills, glass furnaces and plate-glass rollers. Buildings included a tire-making plant, stamping plant, engine casting plant, frame and assembly plant, transmission plant, radiator plant, and a tool and die plant. At one point, the complex even included a paper mill. There was even a soybean conversion plant that turned soybeans into plastic auto parts.

To construct the Rouge, Ford began buying the property in 1915. Originally, the Rouge was intended to support America’s efforts in World War I. In 1917, a three-story structure, Building B, was erected on the Rouge site to build Eagle Boats, warships intended to hunt down German submarines. However, the war ended before the Ford Eagle Boats ever went into action.

The first land vehicles assembled in the Rouge were farm tractors. In 1921, production of the world’s first mass-produced tractor, the Fordson, was transferred from the original Dearborn plant to the Rouge. Production of passenger vehicles came with the production of Model A’s in the late 1920s. Other notable vehicles produced there include the Ford Thunderbird, Mustang and F-150 pickup truck.

The Great Depression didn’t halt production at the plant, but cost-cutting measures did make life harder for workers, which helped give way to the growing union movement. Ford resisted unionization attempts, and believed companies should deal directly with workers. However, auto workers wanted to work together to collectively bargain in order to negotiate better working terms with Ford.

The tension erupted in the famous Battle of the Overpass on May 26, 1937, when a group of union organizers led by Walter Reuther attempted to distribute union literature at the Rouge. Ford security and a gang of hired thugs beat them severely. It would mark a turning point in organization efforts, and Ford would eventually recognize union representation.

During World War II, production shifted to jeeps, amphibious vehicles, parts for tanks and tank engines, and aircraft engines used in fighter planes and medium bombers.

After the death of Henry Ford in 1947, ideas about how to best run an auto company began to change. Instead of having all production concentrated at one plant, new auto leaders — including Henry Ford II — began to develop a decentralized and more global approach. Rather than having all aspects of production in-house, automakers began developing networks of suppliers for their raw materials, and later, auto parts.

Production at the Rouge dwindled. In 1992, the only car still built at the Rouge, the Ford Mustang, was about to be eliminated and assembly operations in Dearborn Assembly terminated. UAW Local 600, which represents workers at the plant, worked with Alex Trotman — then president of Ford’s North American Operations — set out to keep the Mustang in production and to keep production in the Rouge. Together, the company and the UAW established a modern operating agreement and fostered numerous innovations to increase efficiency and quality. The company, for its part, would redesign and reintroduce the Mustang, and invest in modern equipment.

Tours of the Rouge are now offered as part of the Henry Ford Museum on Mondays through Saturdays.

Source : #MIHistory – Jan. 4 – The Rouge, Official Blog of the Michigan House Democrats

On January 4, 1943, Fran Harris became the first woman to broadcast news in Michigan on WWJ radio in Detroit.

In 1931, Fran Alvord Harris began a long and successful career in broadcast journalism when she made her debut as “Julia Hayes” on radio station WWJ in Detroit. As “Julia Hayes” she shared household hints with listeners on a half-hour program for three years. For another women’s program, she played the role of “Nancy Dixon,” offering shopping advice over WWJ and WXYZ. This broadcasting experience and her general visibility at the radio station, positioned her well for a transition into newscasting.

Fran Harris benefited from the effects of the Second World War, as the men left for combat or for war reporting. In 1943 she became the first woman newscaster in Michigan. Three years later Harris pioneered in television when she became the first woman on TV in Michigan. In 1964 she achieved further recognition when she moved into management as features coordinator for WWJ-AM-FM-TV, until her retirement in 1974. Fran Harris blended dedication to her work and commitment to the profession with active involvement in community affairs.

Born in Detroit in 1909, Fran Alvord was the only child of a father who pioneered in the field of orthodontia and a politically active mother. Her close-knit family, which included caring grandparents, provided support for her mother’s state-wide women’s club involvement and her elected position on the local school board. Fran Alvord was educated in suburban Highland Park and attended Grinnell College in Iowa. In 1929, she graduated with a B.A. degree in psychology and English.

Following graduation, Fran Alvord returned to Detroit. She married Hugh W. Harris in 1932. They had three children. In Detroit she began working in the retail business at Himelhoch’s, a local specialty shop. Experience in sales, advertising and personnel prepared her for the roles of “Julia Hayes” and “Nancy Dixon,” consumer-oriented radio personalities who appealed to women audiences. During the Second World War, when WWJ lost several of its male newscasters, Fran auditioned and after some consideration was given the job of reading news on the air. In addition to daytime news, she had her own radio talk show in which she interviewed film, stage, literary, and political figures. In 1949 she received a Peabody Award for a show on sex offenders. She also developed a “traffic court” program on television that was widely copied across the country and was the precursor of “People’s Court.”

Fran Harris continued doing both radio and television broadcasting until 1964, when she moved into management as the features coordinator for WWJ radio and television. She retired in 1974 to assume an active role in her family’s business. She served as treasurer of I. C. Harris & Company (an international transportation firm) from 1957 to 1982, as president and chief executive officer from 1982 to 1984, and as board chair from 1984 to 1985. During these years she also carried on an active role in a wide range of community services, including organizations promoting women’s concerns.

Awards, Honors, and Achievements

- George Foster Peabody Award (broadcast’s Oscar) for her radio program dealing with problems of sexual deviants, 1949.

- Chaired the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in Service.

- The first woman–and only broadcaster–installed in Michigan’s Journalism Hall of Fame in 1986.

- The only woman ever selected to win the Governor’s Award from the National Academy of TV Arts and Sciences (EMMY) in Detroit (1987).

- The national president of Women in Communications, Inc., 1971 to 1973

- Established an Associate Degree in Child Care Administration at Ferris State University.

- Appointed to Status of Women Commission by Governor Swainson in 1963 and then served through 1976 with appointments by Governors Romney and Milliken.

- Author of Focus Michigan Women, 1701-1977 under the auspices of the Michigan Women’s Commission in commemoration of the International Year of the Woman., 1977

Sources :

Anne Ritchie, Washington Press Club Foundation, 1992

Frances “Fran” Alvord Harris – Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame

Broadcast Pioneers, Washington, D.C.

Fran Harris (1909-1998), Papers, 1930, 1943-1976 at the University of Missouri National Women and Media Collection

Sue Carter, “”Women Don’t Do News”: Fran Harris and Detroit’s Radio Station WWJ”, Michigan Historical Review, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Fall, 1998), pp. 77-87

Basil Brown, an African American Democrat from Highland Park and senior member of the Michigan State Senate, pleaded guilty before the Ingham County Circuit Court on December 1, 1987 to one charge of delivering cocaine and one of delivering marijuana to a prostitute at his residence in Lansing. He had numerous drunken driving convictions on his record previously. According to the Michigan Legislative Biography Database, the drug conviction was later overturned by the Supreme Court on the basis of issues of entrapment. However, due to pressure from colleagues in the Michigan Senate, he announced his resignation effective on January 4, 1988.

Brown served in the legislature for more than 30 years before resigning from the Senate in 1988 He was the 1st African American chair of the Judiciary Committee and served in this powerful position for over ten years. He also served as the Democratic Majority Floor Leader.

Known as the “Dean of the Michigan Senate” he was the longest serving senator as of 1/1/1988. He received 3 decorations for his services in US Navy during World War II.

Emily Lawler, “Death, Drugs, and Skullduggery: A Brief History of Michigan Political Scandals“, MLive, August 21, 2015; updated August 24, 2015.

“Michigan State Senator Guilty in Drug Case“, New York Times, December 1, 1987.

Jack Torry, “Career of Michigan Sen. Basil Brown Dissolves in Alcohol, Drug Charges“, Toledo Blade, December 5, 1987.

The Amboy, Lansing and Traverse Bay (ALTB) Railroad is a defunct railroad which operated in the state of Michigan during the 1850s and 1860s. Initially planned as an ambitious land grant railroad which would run the length of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, poor finances and politically-motivated routes frustrated these aims. The AL&TB was one of several railroads chartered in the 1850s to take advantage of a land grant program instituted by the federal government. Under an act of 1856 and successive acts Michigan had in its gift over 5,000,000 acres (20,000 km2) of land which could be given to railroads in exchange for constructing certain routes.

The railroad had failed to reach Lansing at the time the Civil War broke out, so army recruits had to take the stage to Jackson to enlist.

Sources:

Michigan History Magazine, January-February 2016

Amos Gould, born in Aurelius, New York on December 3, 1808. Moved to Owosso, Michigan in 1843

From the time of his arrival in Michigan in 1843, Gould speculated in land, much of which he purchased at tax sales. When the demand for Michigan pine skyrocketed following the Civil War, Gould cut, sawed, and marketed lumber on a rather large scale near Owosso. His brother, David, also was involved in the lumber industry in the vicinity of St. Charles and Chesaning, Michigan.

Gould served as the attorney for the Detroit and Milwaukee Railroad Company, 1852-1881, a position which was quite involved with the acquisition of land for its right-of-way from Pontiac westward to Grand Haven, Michigan. He also promoted the establishment of the Amboy, Lansing, and Traverse Bay Railroad (one of Michigan’s first land grant roads), and directed construction of its first section, from Owosso to Lansing, Michigan.

Finding aid for Amos Gould Family Papers, Clarke Historical Library Central Michigan University.

On January 5, 1870, the University of Michigan Board of Regents voted to allow women to attend their college.

Source: Mich-Again’s Day.

On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford announced he was raising salaries to $5 a day for 8 hours of work, starting June 12.

It was an effort to prevent turnover (close to 400% in 1913) and to ensure that his employees could afford to buy the cars they made. The previous wage was $2.34 for nine hours of work.

The news prompted more than 10,000 people to show up at the company’s Highland Park plant to apply for jobs – some came as early as 3 a.m. the next day.

Men 22 years and older were eligible.

Sources :

Zlati Meyer, This Week in Michigan History, January 4, 2009, B.4.

Michigan Historical Calendar, courtesy of the Clarke Historical Library at Central Michigan University.

John Gallagher, “Henry Ford’s $5 Day creates modern Detroit, causes shift in U.S. society”, Detroit Free Press, January 5, 2013

Ford’s Five Dollar Day, Henry Ford Blog, January 3, 2014.

The Chrysler Six, the first car to bear Walter Chrysler’s name, debuts at the New York Automobile Show.

When Walter P. Chrysler presented the first car bearing his name as a trademark to the public at the New York Motor Show on January 5, 1924, he had pulled off a major coup: his Chrysler Six, marketed with the model designation B-70 because of its top speed of 70 mph, set new standards in the category of mid-sized US cars. What’s more, the first Chrysler became a bestseller – and the foundation stone for Chrysler Corporation.

Over and above this, Walter P. Chrysler reached one of his great personal aims with this car – an aim he had been pursuing since 1908. In that year, he bought his first car, a Locomobile, while still working as one of the youngest top managers in the American railway industry. He disassembled his new acquisition in order to analyze its engineering. According to Chrysler’s biographer, it had been his dream to become active in automotive production from the moment he began disassembling the Locomobile. He decided to turn his back on railway management and to become a motor manufacturer. (Vincent Curcio, “Chrysler – The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius”, 700 pages.)

He pursued his aims with single-minded determination, thereby creating the conditions for the assembly of the first Chrysler cars in the Chalmers plant on Jefferson Avenue in Detroit on brand-new production facilities on December 20, 1923. Even before the public launch at the New York Motor Show, Chrysler was thus able to present the new creation of his team of engineers, Fred Zeder, Owen Skelton and Carl Breer, to a select circle of bankers, suppliers, car dealers and important automotive experts at a trial-driving event.

The new Chrysler Six met with spontaneous enthusiasm. The few skeptics were impressed, at the very latest, after the first trial-driving. One dealer, for instance, expressed his doubts about the car’s alleged top speed of 70 miles per hour. But when Chrysler’s marketing manager Tobe Couture accelerated the test car to 70 mph on a wet road, with the skeptic in the passenger’s seat, then took his hands off the steering wheel and slammed on the brakes to demonstrate the car’s track-holding stability, this dealer was convinced, too. His signature under the purchase contract is said to have been a bit of a scrawl, however; the man was still shaking.

A top speed of 110 km/h may be ridiculous by today’s standards – but it was breathtaking for drivers back in the 1920s. The Chrysler was only insignificantly slower than straightforward luxury cars like the Packard Eight which sold at twice the Chrysler’s price. The Chrysler Six also proved to be highly superior to the competitors in its class in terms of its other design features and qualities, so it assumed the position of “best in class” immediately. In his article entitled “The Chrysler Six – America’s First Modern Automobile”, which appeared in the January 1972 edition of the Antique Automobile magazine, automotive historian Mark Howell wrote that its influence on motor history only compared with that of the Ford Model T, and that this car clearly defined the parting line between ‘old’ and ‘new’ cars in automotive history.

The exhibits in the Walter P. Chrysler Museum in Auburn Hills, Michigan, impressively demonstrate how distinctively this parting line had been drawn. A Chrysler B-70 from the museum fleet, a 1924 Chrysler Six sedan in an elegant three-shade livery of light brown, dark brown and black, had been owned by the descendants of the car’s co-creator, Fred Zeder, for many years. In the past 80 years, the historical jewel has never been completely restored but was merely serviced and repaired before it was acquired by the Chrysler Museum in the 1990s.

Sources :

Michigan History, January/February 2013.

Also see Chrysler : the life and times of an automotive genius / Vincent Curcio. Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press, 2000. Here is a richly detailed account of one of the most important men in American automotive history, based on full access to both Chrysler Corporation and Chrysler family historical records. Chrysler emerges as a man who loved machines, an accomplished mechanic who also had highly developed managerial skills derived from half a lifetime on the railroads, a man whose success came from his deep understanding of engineering and his total commitment to the quality of his vehicles. Vincent Curcio traces Chrysler’s rise from a locomotive wiper in a Kansas roundhouse to the head of the Buick Division of General Motors, to his rescue of the Maxwell-Chalmers car company, which led to the successful development of the 1924 Chrysler–the world’s first modern car–and the formation of Chrysler Corporation in 1925. Chrysler was quite different from the other auto giants–a colorful and expansive man, deeply involved in the design of his cars, a maverick in establishing his headquarters in New York City, in the world’s most famous art deco structure, the fabled Chrysler Building, which he built and helped to design. Because of his emphasis on quality at popular prices, the company weathered the Great Depression with flying colors–losing money only in the rock-bottom year of 1932–and despite the market fiasco of the Chrysler Airflow (which was years ahead of its time), the company grew and remained profitable right up to Chrysler’s death in 1940. The definitive portrait, Walter P. Chrysler is must reading for all car enthusiasts and for everyone interested in the story of a giant of industry.