On April 27, 1763 Ottawa leader Pontiac led a historic effort to bring disparate tribes together to drive the Redcoats from their land. A council was held on the shores of the Ecorse River, about ten miles southwest of Detroit. Using the teachings of the Indian prophet Neolin to inspire his listeners, Pontiac convinced a group of Ottawas, Chippewas, Potawatomis, and Hurons to join him in an attempt to seize Fort Detroit. On April 27, 2013, 250 years to the day, a commemorative event honoring this council was held in Council Point Park in modern day Lincoln Park.

On the anniversary, local officials dedicated a new Michigan historical marker for Pontiac’s Council in a Michigan Division of Natural Resources ceremony.

As part of the celebrations, Chief Pontiac descendant Rudy Pontiac, 72, talked about his ancestor and the current plight of American Indians.

“He did a great thing, you know, unite the tribes and tell his people that they are taking all the land away from us and we won’t have anyplace to go,” Pontiac, who retired from General Motors after working in product development and civil rights, said recently from his home in the Grand Rapids area. “It’s a bad thing that happened to my people.”

Chief Pontiac tried to organize the American Indians to capture the British forts in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions and force them out. They successfully seized nine forts, but eventually were overtaken by Europeans and colonial Americans.

Listen to audio, Michigan Radio interview (April 24, 2013) with Ben Hinmon, Cultural Instructor of the Seventh Generation Program of the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe in Mount Pleasant. Hinmon is the Great-Great-Great-Great Grandson of Chief Pontiac.

Sources :

Michigan History, March/April 2013.

For another article, see Tammy Stables Battaglia , “American Indians to gather in Lincoln Park to honor Chief Pontiac“, MLive, April 22, 2013.

On April 27, 1764, the Provincial Grand Master of the Free and Accepted Masons in New York issued a charter to a Masonic lodge in Detroit. The Royal American Regiment’s Lieutenant John Christie was the master of the lodge, Michigan’s first and the first one established west of the Allegheny Mountains.. The Detroit Masons first adopted the name Zion Lodge in 1794 when they operated under a new charter from Quebec. With American occupation of Michigan, the lodge again came under the Grand Lodge of New York, which issued a new charter in 1806 to “Zion Lodge No. 1” of Detroit. This name was retained by the Grand Lodge of Michigan when it was formed in 1826. Zion Lodge suspended operations during the War of 1812 and during the anti-masonic agitation on 1829-1845, but each time its functions were resumed.

Sources:

Michigan Historic Marker : Registered Site S0255 Erected 1964 Location: 500 Temple Avenue Detroit, Wayne County

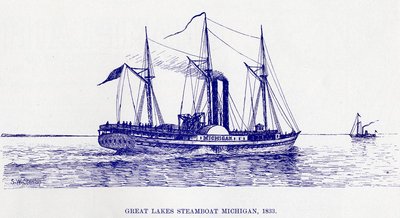

On April 27, 1833, the steamboat Michigan, the first steamer built in Detroit and the most- advanced Great Lakes passenger vessel of its time, was launched from Detroit.

Source: Mich-Again’s Day

Two members of Company K, 1st Michigan Sharpshooters – Louis Miskoguon and Amos Ashkebugnekay (along with 250 others from Michigan) — were aboard the Sultana when it exploded and burned. How ironic. After surviving the horrors of the Confederate Prison at Andersonville, Georgia, to face death a second time on the way home to Michigan. Fortunately they were able to swim ashore and may have walked the rest of the way home.

It was the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history, more costly than even the April 14, 1912 sinking of the Titanic, when 1,517 people were lost. But because the Sultana went down when it did, the disaster was not well covered in the newspapers or magazines, and was soon forgotten. It is scarcely remembered today.

April 1865 was a busy month; On April 9, at Appomattox Couthouse, Virginia, General Robert E. Lee surrendered. Five days later President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. On April 26 his assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was caught and killed. That same day General Joseph Johnson surrendered the last large Confederate army. Shortly thereafter Union troops captured Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The Civil War was over. Northern newspapers rejoiced.

News of a terrible steamboat tragedy was relegated to the newspaper’s back pages. In a nation desensitized to death, 1,700 more did not seem such an enormous tragedy that it does today.

The accident happened at 2 a.m., when three of the steamship’s four boilers exploded. The reason the death toll was almost exactly equal to the number of Union troops killed at the battle of Shiloh (1,758) was gross government incompetence. The Sultana was legally registered to carry 376 people. She had six times more than that on board, due to the bribery of army officers and the extreme desire of the former POWs to get home.

Sources:

Who was who in Company K, 2010, by Chris Czopek.

Remembering Sultana from Stephen Ambrose, Expedition Journal, National Geographic News, May 1, 2001.

Philip P. Mason and Paul J. Pentecost, “From Bull Run to Appomattox : Michigan’s Role in the Civil War. Detroit, MI : Wayne State University, 1861 includes a chapter on the sinking of the Sultana.

On April 27, 1915, the wooden bridge to Detroit’s recreational park, Belle Isle, burned, stranding 1,000 visitors and 100 vehicles on the island. Detroit and Windsor ferry boats left their cross-river runs to evacuate the stranded.

Sources : MIRS Capitol Capsule, April 27, 2021.

On April 27, 1938, more than half of Oxford High School’s 300 students refused to attend classes and paraded through the streets carrying banners protesting the school’s decision to drop the football program for a year for economic reasons.

Superintendent R.W. Zinn asked the students to return to class, but they refused, shouting for a contract to be offered to the football coach. Students who wanted to attend classes had to cross a picket line.

The Oxford School Board decided to invest its limited resources to keeping the high school band because its success “has made Oxford more music minded than football minded,” according to the board. However, after the protest, the board reversed course and reinstated football as long as the players’ parents agreed to release the school of liability in case of injuries.

Source: Detroit Free Press

Michigan was not required to pay for a prisoner’s sex change operation, according to a decision by state Attorney General Frank Kelley on April 27, 1976.

A query had come from state Department of Corrections Director Perry Johnson about inmate James Silva, who was serving 25-50 years for assault with intent to commit armed robbery and was up for parole in January 1981. Johnson called it “an unprecedented case” for his department.

According to a psychiatric consultant’s report, Silva, who preferred the name Sherry and once tried to self-mutilate, fit all the criteria of a transsexual. He “believes that he is the opposite sex mentally from what his body is,” devoted most of his time in the previous two years to finding out where he could have gender reassignment surgery after prison, and “has done everything he can to assume the trappings of a female,” such as wearing women’s shoes, plucking his eyebrows, wearing lipstick and “using a higher, more feminine tone of voice.”

In Kelley’s decision, he wrote that inmates have a constitutional right to essential medical treatment, but that “the treatment requested cannot be considered essential medical treatment.”

For the full article, see Zlati Meyer, “This week in Michigan history: A decision on who pays for inmate’s sex-change surgery”, Detroit Free Press, April 27, 2014.

Here’s a game: which of these political, athletic or entertainment celebrities did not appear in Michigan’s Capitol to testify or appear before a committee, a rally or a special session:

Jim Brown

Howard Jarvis

Ted Nugent

Sr. Helen Prejean

Willie Nelson

Al Kaline

Ward Connerly

Magic Johnson

George Cadle Price

Cesar Chavez

Jack Valenti

Muhammad Ali

Now think about it for a moment. Ready? Okay:

Jim Brown. Possibly the greatest running back in football history, and by all accounts the greatest lacrosse player ever, Mr. Brown just sort of materialized at the back of the Senate chamber in 2007, where he shook hands but was never introduced from the podium. He was in Lansing to promote a program aimed at ending gang violence.

Howard Jarvis. The father of the California tax cut movement, and later a fabled extra on “Airplane,” Mr. Jarvis spoke to a rally of several thousand people from the Capitol steps shortly after the success of Proposition 13 in 1978. He encouraged support for tax cut drives then moving through Lansing.

Ted Nugent. The Motor City Madman, rock and roller, fanatic gun and hunting advocate, and right wing icon, has been something of a fixture in Michigan politics for several decades. But he actually testified in 1998 before a committee chaired by then Sen. David Jaye for expanded concealed weapons rights. It was insulting, he said, to have to go to gun board to get a concealed weapon permit when his Second Amendment rights were “guaranteed by the Constitution but given to me by God.”

Sr. Helen Prejean. The internationally renowned opponent of capital punishment and author of “Dead Man Walking” was invited by then-Sen. George McManus to help rally opponents of the death penalty. There was discussion of starting a petition drive to allow for capital punishment. At a press conference, Ms. Prejean was challenged by Mr. Jaye, who was a bit tongue-tied against the better prepared Ms. Prejean.

Al Kaline. The Detroit Tigers great was enthusiastically welcomed by both chambers of the Legislature after his election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Ward Connerly. The face of the effort to end affirmative action in California was in Michigan several times as the state went through a campaign to end affirmative action constitutionally. After one committee appearance, Mr. Connerly got into an informal but intense debate with then-Sen. Virgil Smith (now a judge and father of the recently resigned Sen. Virgil Smith).

Magic Johnson. Reaching the House podium following a massive parade when the Michigan State University men’s basketball team won the 1979 NCAA men’s basketball championship (in a game with Indiana State and Larry Bird that changed the scope of the sport), the then sophomore Mr. Johnson said he hoped people would support MSU “whether I go or I stay.” Reporters looked at each other and said, “He’s going to the NBA.”

George Cadle Price. WHO? Mr. Price was the first and one of the longest-serving prime ministers of Belize. It’s not exactly clear why he was in Lansing in 1979, other than to promote tourism and economic development. A House staff member who oversaw what was known as the document room played a big role in getting him a chance to speak to the House chamber when session was not in, and then desperately dragooned other staff, reporters and tourists into the chamber to hear Mr. Price speak.

Cesar Chavez. The leader of the farmworker’s movement spoke to the House in late 1979. He was soft spoken, wore a work shirt and pants, spoke of how the workers felt they had a mission to bring food to all people and completely enraptured everyone who heard him.

Jack Valenti. Best known as the president of the Motion Picture Association of America, and a fixture of the annual Oscars broadcast, Mr. Valenti had also been a top aide to former President Lyndon Johnson. He appeared to speak before the House Judiciary Committee in the early 1980s against a bill to regulate movie theaters. A very sharp dresser, Mr. Valenti also surprised people because he was, ah, less tall than expected.

Muhammad Ali. The Greatest. He came to the Legislature in 1997 to promote efforts for greater protections for children. Because of his Parkinson’s disease, he did not speak himself but an assistant delivered his testimony. And probably no person attracted more attention to his appearance than Mr. Ali. People were desperate to meet him, and he was thoroughly gracious.

Willie Nelson. Okay, you’re thinking he spoke about legalizing marijuana or urged farmer rights. But beyond playing in a number of venues in the Lansing area, he did not appear before a rally or the Legislature. If you picked him, you win.

Source: John Lindstrom, “Which Of These Celebrities Did Not Appear Before The Legislature?”, Gongwer Blog, April 27, 2017.

The Lansing Republican, the earliest precursor to the Lansing State Journal, published its first edition on April 28, 1855.

The weekly newspaper was started by Henry Barns, a strong abolitionist and a founding member of the Republican Party in Michigan. Barns arrived by stagecoach on April 24, 1855, the same year work began on the Agricultural College of the State of Michigan, which became Michigan State University.

Four days later, the first edition of the paper was published. Barns would publish only one more issue before selling the paper and returning to Detroit. But now, Lansing had a weekly Republican paper in competition with the Democrat paper, the Lansing Journal. The paper’s first office was a log cabin at the corner of Washington Avenue and Ionia Street.

The new owners, Rufus Hosmer and George Fitch, both pledged support for the anti-slavery movement.

Over the subsequent decades, the name of the paper would change almost as often as the publishing site. A long succession of owners and editors would parade into and out of the picture, but the newspaper offices were always in, or close to downtown Lansing.

The Lansing Republican became the State Republican. When it began publishing two editions daily in 1910, its Democratic competitor suffered, and in 1911, the State Republican absorbed the Lansing Journal. A new newspaper, the State Journal, was born.

Ard Richardson and Charles Halsted bought the paper in 1914 and moved it to new headquarters at Grand Avenue and Ottawa Street,where it remained for more than 30 years.

Soon radio and television filled the air waves with news, and the State Journal needed to publish and distribute the paper faster.

Under the direction of longtime publisher Paul Martin in the late 1940s, plans for a new newspaper plant came together, and, in 1951, the paper had a new home at 120 E. Lenawee St. It was the Journal’s first newspaper plant, housing all facets of the operation.

The newspaper’s name became the Lansing State Journal in 1984 and in 1994, LSJ opened its first production facility in Delta Township. That facility closed in the summer of 2014.

The Lansing State Journal will move its offices to the Knapp’s Centre in January.

For the full article, with photos, see Vickki Dozier, “Lansing State Journal History”, Lansing State Journal, November 28, 2015.

I owe former Rep. Monte Geralds an apology.

Mr. Geralds was expelled from the House in 1978 after being convicted of embezzling from a law client. As I have previously written, he undertook his expulsion with dignity and grace. He was the first legislator in Michigan history to be expelled.

Or so I thought, and have reported for 37 years. So too did all the reporters covering the expulsion, so too did the legislators acting on the expulsion (which helped define the weight they felt when acting on the expulsion). And when the Senate expelled Sen. David Jaye in 2001, we again referred to Mr. Geralds as the first. And with expulsion talk swirling on Rep. Todd Courser and Rep. Cindy Gamrat, again we reported Mr. Geralds was the first.

But we were wrong, and thanks to a research librarian at the Library of Michigan we know now that the first legislator expelled in Michigan was Rep. Milo Dakin of Saginaw, a shingle inspector, serving his second term in the House when he was expelled in April 1887 for trying to bribe his colleagues.

Milo Dakin. Who was this fellow, this nefarious blackguard who so besmirched the House that the 94 members present and voting in the evening of April 28, 1887 (Mr. Dakin was present, but did not vote) decided unanimously to expel him, only to have him vanish in a way from history?

Well, he was an orphan at 13, a war veteran at 16, a laborer who worked on a farm, in mills and in the winter months in the woods as a shingle inspector. And who at 26 he was elected to the House as a fusion candidate, when the Greenback Party and the Democrats ran together.

From the Michigan Manual of 1887, Mr. Dakin describes himself thus: “His early years were such as usually fell to the lot of the children of our early pioneers. His parents both dying when he was but thirteen years of age, he was thrown upon his own resources. At fifteen he enlisted in Company C, Ninth Regiment Michigan cavalry, and served until the close of the war, eighteen months in all.” His little biography does not say, but in testimony during his House trial he pointed out that his regiment was attached to the army of William Tecumseh Sherman. So, with Mr. Sherman, Mr. Dakin marched to the sea, fighting in the engagements that leveled Atlanta and captured Savannah and effectively destroyed the Confederacy’s economy. He was discharged honorably.

He had no real education. After the war, he worked on a farm in Ionia County, then a sawmill in Montcalm County before removing to Saginaw County where he worked the saw mills in the summer and inspected shingles in the winter, and did this while serving in the House.

So what got him into trouble?

The House Journal that includes his trial and blustering oratory leading up to his expulsion vote is available online. Essentially, the city leaders of Saginaw wanted the Legislature to enact changes to their charter, and Mr. Dakin was expected to be one of the people to make that happen. How the charter was to be changed was not clear from the brief research.

It also appears Mr. Dakin offered a substitute to the Saginaw bill which horrified the city leaders. What it contained and why it so horrified the Saginaw fathers is also unclear. However, one does wonder if that substitute wasn’t part of what happened next.

Mr. Dakin was accused of getting money from Saginaw leaders, politicians and private citizens, to give to legislators and to help come up with names that could benefit from the money. Mr. Dakin was then accused of writing down a list of lawmakers and putting a price next to them. For the times it was probably big money, but the anticipated bribes ranged from $5 to $25.

Mr. Dakin acknowledged he was getting money from the Saginaw leaders, and expected the money, but it was to put on a dinner at the Eichele House, his Lansing rooming house, ostensibly to convince lawmakers to vote for the bill. The prosecution questioned how different amounts could be allocated to different men if it was all supposed to go for a “feast.” There were also accusations about spending it all on beer and cigars (which would have bought a lot of both at the time) and Mr. Dakin walking with a confederate to “North Lansing.” What that reference means is unknown, though the city had several houses of ill repute and one could wonder if it was a nudge-nudge-know what I mean statement.

Another remarkable thing about the expulsion was how quickly the House handled it. In little more than a week after charges were made, the House held a trial on the floor (after appropriating $200 to Mr. Dakin to hire his lawyers) and then voted to expel him.

In arguing for his expulsion, Rep. Gerrit Diekkema of Holland said, “I am also sorry for poor Dakin. God knows I am sorry for him; but the reputation of ninety-nine men sitting here in the Legislature of the State of Michigan should rise high above all feelings of mere sorrow for one man.” Their duty, he said, was to protect the good name of Michigan, instead of showing sympathy for one man who admitted he had done wrong.

Little is known of Mr. Dakin after he left the Legislature. He apparently stayed in Saginaw, married and had two sons. His wife died a number of years before him, and he died in 1927, eight years before Mr. Geralds was born.

For the full article, see John Lindstrom, “Okay, Correction, The First Legislator Ever Expelled Was…”, Gongwer Blog Post, September 3, 2015.