The 1st Michigan Regiment mustered at Campus Martius in Detroit on this date in 1861, called by Abraham Lincoln to protect the nation’s capital. After the regiment received its flags, made by the women of Detroit, they boarded a ship for Cleveland, then took the railroad to Washington, D.C. According to legend, President Lincoln said “thank God for Michigan” upon seeing the Michigan First arrive, the first troops arriving from the western states to reinforce the Capitol.

For the full article, see Scott Pohl, “MICHIGAN AND THE CIVIL WAR: 150th anniversary of the Michigan First”, WKAR News, May 11, 2011.

On May 1, 1915, the City of Detroit mandated that all milk be pasteurized. Probably as a direct result, along with improved milk facilities and supply, the health department announced in 1921 that baby death rates from diarrhea and enteritis had dropped by half

Source : Bill Loomis, On This Day in Detroit History, 2016.

Michigan voters approved a prohibition amendment to the State’s constitution before national prohibition became effective. However, home production of alcohol and speakeasies quickly became popular.

At downtown Detroit’s Richter’s Café on State Street, a single empty bottle hung suspended upside-down from a swathe of black crepe. Pinned to the bottle was a bedraggled bouquet of faded asters dimly lit by a red lantern. The doors were locked, the windows shuttered, and the lights extinguished inside.

King Alcohol was dead.

Michigan’s May 1, 1918 enactment of Prohibition made Detroit the first major city to abolish alcohol. The factors leading up to the law had as much to do with political and economic machinations as with moral and social influences.

Sources :

Michigan Historical Calendar, courtesy of the Clarke Historical Library at Central Michigan University.

To Drink or Not to Drink, Historically Speaking, Detroit News Photo Gallery.

Mickey Lyons, “Dry Times: Looking Back 100 Years After Prohibition“, Hour Detroit, April 30, 2018.

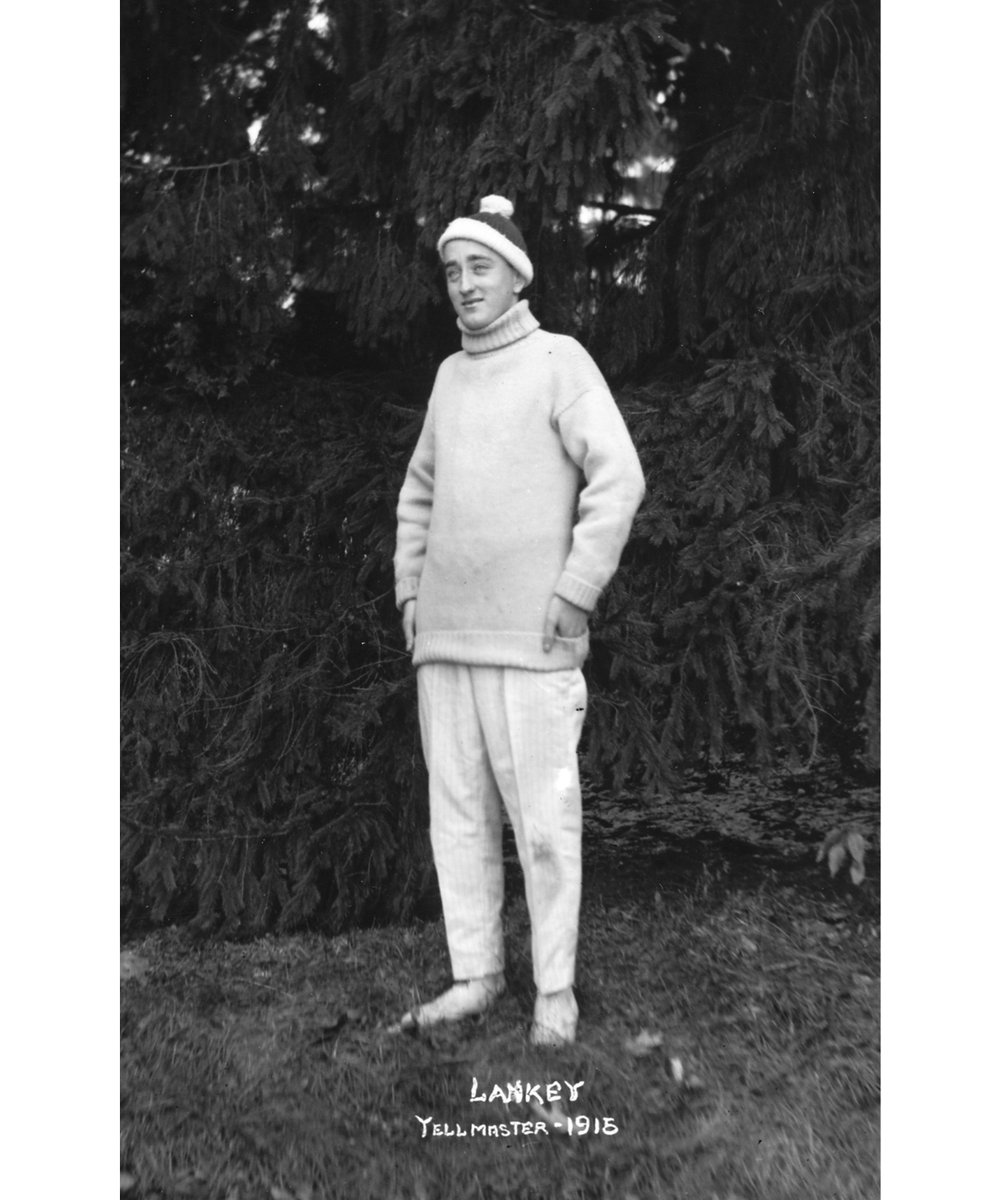

Part of World War I airman Francis I. Lankey’s legacy was the creation of the fight song for Michigan State University.

Lankey was born in Bay City in 1896, the only child of Bertha and Willis Lankey, who resided on State Street. Before World War I, he entered Michigan Agricultural College, the forerunner to Michigan State University, and was a member of the MAC College of Engineering class of 1916. The blue-eyed young man became the “yellmaster,” or head cheerleader for the “Aggies” football team. He also was an accomplished musician, playing ragtime piano at various places around Lansing.

“He knew there was no fight song to be played at the football games,” Higgs said, adding that he wanted something to compare to Michigan’s “Hail to the Victors” or “On Wisconsin.”

So, Lankey wrote one — the same fight song played today and is so familiar to everyone who ever attended MSU or who has heard the MSU Marching Band.

“Go right through for MSU,” the familiar chant today originally stated “Smash right through that line of blue” (meaning the U of M Wolverines). He wrote the song so the opponent’s name would be inserted and a few lines adjusted to accommodate the undesirable aspects of the visiting team.

When America entered World War I, Lankey registered for the draft and at the age of 21 began training as an Army pilot. Since he had an engineering degree and had worked in Lansing for the state of Michigan as an engineer for a year, he was a top candidate as a combat pilot.

Commissioned 1st lieutenant, Lankey learned to fly the Curtiss JN-4 Jenny and was assigned to Carlstrom Field in Florida where he flew his plane in the flying circus, an Army Air Corps demonstration team, raising funds in air shows for the Victory Loan program to help repay the wartime debt.

On May 1, 1919, his plane, which featured red-white-blue tail design, had a damaged propeller and a new one replaced it. Lankey took the plane up to test it and witnesses on the ground said they saw the plane burst into flames and drop to the ground. Lankey died in the wreckage from extensive burns, according to medical personnel.

Although his career in the Army Air Corps might not have been stellar, he should be remembered by all True Spartans!

Robert Bao, “The MSU Songs: Smashing Right Through the Myths”, MSU Alumni Association, August 26, 2013.

Tim Younkman, “Bay City World War I veteran’s legacy is MSU fight song”, Bay City Times, November 11, 2011.

Spartan Marching Band History, MSU Fight Song.

On May 1, 1926, Ford Motor Company becomes one of the first companies in America to adopt a five-day, 40-hour week for workers in its automotive factories. The policy would be extended to Ford’s office workers the following August.

Henry Ford’s Detroit-based automobile company had broken ground in its labor policies before. In early 1914, against a backdrop of widespread unemployment and increasing labor unrest, Ford announced that it would pay its male factory workers a minimum wage of $5 per eight-hour day, upped from a previous rate of $2.34 for nine hours (the policy was adopted for female workers in 1916). The news shocked many in the industry–at the time, $5 per day was nearly double what the average auto worker made–but turned out to be a stroke of brilliance, immediately boosting productivity along the assembly line and building a sense of company loyalty and pride among Ford’s workers.

The decision to reduce the workweek from six to five days had originally been made in 1922. According to an article published in The New York Times that March, Edsel Ford, Henry’s son and the company’s president, explained that “Every man needs more than one day a week for rest and recreation….The Ford Company always has sought to promote [an] ideal home life for its employees. We believe that in order to live properly every man should have more time to spend with his family.”

Henry Ford said of the decision: “It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either ‘lost time’ or a class privilege.” At Ford’s own admission, however, the five-day workweek was also instituted in order to increase productivity: Though workers’ time on the job had decreased, they were expected to expend more effort while they were there. Manufacturers all over the country, and the world, soon followed Ford’s lead, and the Monday-to-Friday workweek became standard practice.

Many think that the 5 day work week should be credited to Henry Ford. However, others note that the first five-day work week in the United States was instituted by a New England cotton mill in 1908 so that Jewish workers would not have to work on the Sabbath from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday. So one has to decide which had more impact : a New England cotton mill or one of largest manufacturers in the country!

In 1929, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America Union was the first union to demand a five-day workweek and receive it. After that, the rest of the United States slowly followed, but it was not until 1940, when a provision of the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act mandating a maximum 40-hour workweek went into effect, that the two-day weekend was adopted nationwide

Sources :

President John A. Hannah presented a charter to the 1st Negro social fraternity at Michigan State College, Alpha Phi Alpha. Herbert Burnett of Detroit was President of the fraternity.

Source: Detroit Free Press, April 30, 1948, p.13

On May 1, 1981, General Motors held groundbreaking ceremonies for a controversial $600 million, 465.5-acre plant in Hamtramck’s Poletown, one of Detroit’s oldest neighborhoods. Approximately $200 million in federal funds were used to acquire the neighborhood and uproot 3,500 residents whose small businesses, churches and schools were razed to make way for the plant.

Source: Mich-again’s Day

More Background

Auto giant General Motors wanted Poletown’s 465 acres for a brand new plant straddling the line between Detroit and the nearby town of Hamtramck. Detroit Mayor Coleman A. Young Jr. was on board, offering to use a new eminent domain law to grab the 1,500 homes and hundreds of businesses. The auto unions were also game. Even the city’s Catholic Archdiocese supported the project, offering to sell off Immaculate Conception Church, the neighborhood parish where mass was still conducted in English and Polish.

But the neighbors were not having it. Led by the Rev. Joseph Karasiewicz, Immaculate Conception’s quiet and humble priest, a loose coalition battled the plant that spring. Defying his own cardinal, Karasiewicz and his allies worked day and night from metal desks in the church basement, searching for a way to save Poletown.

“It’s wrong to cooperate with this type of law in any sort of way,” Karasiewicz told The Washington Post in June 1981. “No one is safe except the man who has the money, to put it bluntly.”

The Poletown standoff would go down as a landmark battle royal pitting residents against American industrial might. The controversy landed in the national spotlight, sparked a legal battle and eventually ended with a dramatic SWAT raid on Immaculate Conception to clear out holdouts.

Although today the neighborhood is long gone, the legacy clinging to Poletown has suddenly been reignited following the dramatic news that GM is planning to close five factories and lay off 15,000 workers in North America. The Detroit-Hamtramck Assembly Plant will cease production, putting 1,540 workers in jeopardy, the Detroit Free Press reported.

Interestingly, the fates of both the plant and the neighborhood destroyed at its expense hinge on the same question: What is the true cost of the sweetheart deals between local governments and industry in the long run?

“They destroyed homes and churches and local businesses, all to build that plant,” Karen Majewski, the mayor of Hamtramck, told Reuters on Monday. “Now that the plant is going to close, people will wonder why that neighborhood had to be sacrificed in the first place.”

The proposal for the new plant in the early ’80s came as Detroit was starting to slip from the heights of its postwar manufacturing power. As the Detroit News recounted in 2000, by 1980, auto plants were beginning to close in the region. The GM plant in the Poletown area was designed to replace an aging Cadillac factory, and the proposal would keep 6,000 jobs within the city limits. It would be GM’s first new factory construction in Motor City in decades.

Poletown also was beginning to feel seismic shifts. Originally settled by Polish immigrants in the 1870s, the neighborhood exploded in the 1920s and 1930s with Polish workers who arrived to labor in Detroit’s auto factories. By the 1980s, the original Polish population was grayer and dwindling, and the neighborhood was also now home to a mix of Albanians, Slavs, Filipinos and African Americans, the News reported.

When Detroit first offered residents a buyout for the GM project, many jumped at the opportunity to relocate to nicer suburbs outside the city. As The Post reported in 1981, the city paid as much as $12,000 for older homes ($34,289 in today’s currency), with an added $15,000 ($42,861 today) relocation fee. But the unwilling did not have much choice: Under the eminent domain law, they were forced to sell. In total, the project threatened to uproot more than 4,000 people.

A backlash stirred among residents who did not want to go.

“We’re fighting the UAW, we’re fighting GM, we’re fighting the city government, we’re fighting the state government, and we’re fighting the church,” a Poletown resident told The Post. “We’re fighting the power structure in this city. It’s an uphill battle.”

The David-vs.-Goliath spectacle drew a colorful assortment of players. John Saber, a retired photographer who had lived in his home for 46 years, refused the city’s offer of $15,000 for his property, the News reported. Instead, he began building a wall around his house and patrolled the front yard at all times with a .22-caliber rifle to scare off looters. He eventually sued the city for $15 million.

“Acting as his own lawyer, he claimed damages for, among other things, destruction of a miraculous apparition on his window sill, his ‘prize’ cats being eaten by dogs abandoned by departing neighbors and an art studio that he would have built on the empty lot next door,” the News wrote.

The standoff also popped up on the radar of Ralph Nader, the crusading lawyer who had gone head-to-head with auto manufacturers like GM over product safety. As James T. Bennett documented in his book “Corporate Welfare: Crony Capitalism That Enriches the Rich,” Nader dispatched volunteers and lawyers to Detroit to help the neighbors in their various legal challenges. He saw the proposal as an example of the vampire capitalism bleeding American communities dry.

“Now, even the wealthiest multinational corporations such as General Motors prepare a prospectus for building a plant and then dangle it before various municipalities and states to ascertain how large a subsidy the taxpayers will be compelled to provide if they want the plant in their area,” Nader wrote at the time.

But Immaculate Conception’s Karasiewicz was very much the public face of the fight. A 59-year-old Detroit native and son of a Ford Motor Co. janitor, the priest openly expressed outrage when his devoted flock was booted from their hard-earned place.

“This is worse than the Communists in Poland,” the priest said, according to Bennett’s book. “To go down to a very basic definition of stealing, it is simply taking other people’s property against their will, and this was taken away from them, the people, against their will.”

Karasiewicz’s position pitted him against church authorities. The archdiocese wanted the GM plant built. “The overall good of the city is achieved by cutting away a certain part,” a church leader said. “When you’re trying to make something grow, you prune.”

Eventually, a legal challenge against the use of eminent domain filed by residents was shot down by the Michigan Supreme Court.

Poletown was effectively done, but Immaculate Conception would be the site of the neighborhood’s last stand.

Church authorities told Karasiewicz that the congregation’s final mass would happen May 10, 1981. According to Bennett’s book, 1,500 worshipers filled the pews. Karasiewicz was ordered to leave the property by June 17. He obeyed, but refused to hand over the church records, The Post reported.

A number of holdouts remained inside Immaculate Conception after the priest vacated, occupying Poletown’s last standing touchstone as a final act of defiance. The sit-in lasted 29 days.

Then, as morning broke on July 14, SWAT teams gathered outside the church while Detroit police closed off the empty residential streets nearby. Tipped off by sympathetic officers about the raid, the protesters inside bolted the doors and began clanging the church bells. Police hooked the door to a tow truck to breach the blockade. Sixty officers stormed the church. Twenty protesters were hauled out, according to Bennett, including a number of elderly women whispering the Hail Mary.

Immaculate Conception was brought down soon after, and construction on the GM plant began. Saber, the gun-toting holdout, was forcibly evicted in March 1982. The facility’s first car — a Cadillac Eldorado — sailed off the assembly line at 12:05 p.m. on Feb. 4, 1985. In the ensuing decades, the plant’s fortunes rose and fell with the U.S. auto industry, a cumulative long slide that continued with Monday’s dark announcement.

Karasiewicz ended up as a sad coda to the Poletown fight. Five months after his church was razed, the priest tumbled over dead from a heart attack.

Source: Kyle Swenson, “Thousands lost their homes in epic fight to build GM’s Detroit plant. Now it’s closing.”, Washington Post, November 27, 2018

For another article, see Jenny Nolan, “Auto plant vs. neighborhood: The Poletown battle”, Detroit Free Press, January 27, 2000.

Briuan McKenna, “We All Live in Poletown Now”, CounterPunch, March 9, 2006.

Poletown : a community betrayed / Jeanie Wylie. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, c1989.

For a movie, see Poletown lives! / presented by the Information Factory ; George Corsetti, producer/director ; assistant director/writer, Jeanie Wylie. Detroit, Mich. : Information Factory, c1982. Documentary that tells, from the residents’ point of view, the story of Poletown, an inner-city Detroit neighborhood that was destroyed in 1981 when the city used its power of eminent domain to turn the land over to General Motors for construction of a Cadillac plant. Shows the changes in attitudes as the people realized that the institutions they trusted — the courts, the United Auto Workers, the church, the City Council, and the media — were not going to help them.

“Private Property and Public Use: Poletown Neighborhood Council v Detroit (1981) – 10 Mich 616”, Michigan Bar Journal, March 2009, pp.18-23.

The following story appeared in the May 1, 1997, edition of Gongwer News Service/Michigan Report:

Accolades were heaped on former heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali Thursday, who appeared before the Legislature to praise the efforts of the state’s children’s ombudsman to combat child abuse and neglect.

Known as “the Greatest” during his legendary boxing career, Mr. Ali was called one of the greatest citizens of Michigan by Lt. Governor Connie Binsfeld during his appearance before the Senate. Mr. Ali lives in southwestern Michigan. His wife, Lonnie, was unable to attend the day’s activities as planned because she had flu.

“I can think of no finer citizen for the abused and neglected children in Michigan than the Greatest,” Ms. Binsfeld said. “And it will take the best to win the uphill battle of ending abuse and neglect of children.”

Afflicted with Parkinson’s disease, Mr. Ali did not speak during his appearances but watched with keen interest at the attention he gathered. Dressed in a gray suit and red patterned tie, and accompanied a personal assistant and several security aides, Mr. Ali moved carefully down the center aisle of the Senate after receiving an award, shaking hands by taking a legislator’s right hand in his left and then extending his right hand.

Mr. Ali, whose testimony to a joint meeting of Senate and House committees was read by Kim Forburger, an assistant to the family, was promoting public support for the recommendations of Children’s Ombudsman Richard Bearup as well as other proposals by Ms. Binsfeld’s Children’s Commission.

Sources:

Paul Lindstrom, Gongwer Blog, June 6, 2016.

“Muhammad Ali Fights Against Child Abuse“, Psychiatric News”, June 6, 1997.

As of May 1, 2010, smoking is generally prohibited in Michigan public places, places of employment and food service establishments. Exceptions have been made for cigar bars and tobacco specialty stores and for gambling areas of casinos if in existence on May 1, 2010. Here you will find more detailed information about the law, its exemptions, frequently asked questions, tools for communities to prepare for the law, and tobacco dependence treatment information for business and citizens.

Employers and restaurants should have done the following:

- Remove ashtrays and other smoking paraphernalia from the workplace.

- Post “no smoking signs” and place them at each entrance to the workplace and throughout the building and work areas.

- Update personnel policies and handbooks

- Inform employees, vendors, customers, or visitors that smoking is prohibited by law and subject to penalties

- Ask any employee or individual smoking in violation of the law to stop, and request that they leave the work area if they refuse

- Train employees and/or supervisors on how to handle individuals who are in violation of the law

The League website will be updated frequently as it receives more information.

Resources:

State of Michigan, Department of Community Health

The Dr. Ron Davis Smoke Free Air Law

“[NO SMOKING] New Michigan Law Bans Puffing in the Workplace,” Miller Canfield

“Michigan Smoking Ban Becomes Effective: Is Your Workplace Ready?” Clark Hill

“The New Michigan No Smoking Law: What Every Employer Must Know,” Nemeth Burwell

“No Ifs, ands or butts – employers need to be ready to go smokefree,” Bodman, LLP

“Michigan’s New Smokefree Law, What You Need To Know,” American Cancer Society

Source: Michigan Municipal League