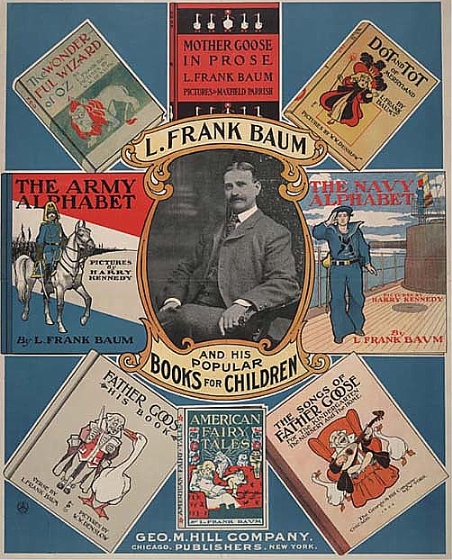

L. Frank Baum reads while sitting in a rocking chair on the porch of his Macatawa summer home, nicknamed The Sign of the Goose.

L. Frank Baum, author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, was born on May 15, 1856. The Holland Sentinel has an excellent feature on Baum’s Michigan connection.

For his family and friends, he was always known as Frank. As an actor and playwright, he was known as Louis F. Baum. As a newspaper editor, he was known as L. F. Baum. And a one of the most popular children’s book authors ever, he was known as L. Frank Baum. But in the resort community of Macatawa, however, Baum was known by another name: “The Goose Man.”

The Wizard of Oz rolled off the presses on May 17, 1900, but Baum actually had the top selling children’s book of the year one year earlier:

In 1899, Baum published “Father Goose: His Book.” The collection of children’s poems exploded in popularity and provided Baum with wealth and prestige for the first time in his life, his great-grandson, Bob Baum, recalled.

The author used the profits from his book to rent a large, multi-story Victorian summer home nestled on the southern end of the Macatawa peninsula on Lake Michigan.

The home, which he eventually purchased, came to be known as the Sign of the Goose, an ever-present reminder of the fame that came along with “Father Goose.”

Members of the MSU community can read the complete text of Father Goose right here. Others may have to try interlibrary loan.

Here’s a link to Baum’s 1907 novel Tamawaca Folks: A Summer Comedy, lampooning the resort community.

Also see the Oz Club Facebook page for all kinds of photos & history.

Sources:

L. Frank Baum, The Goose Man of Macatawa , Absolute Michigan.

Children begged for more and Frank Baum delivered, with 13 sequels to “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz”. Martin Chalakoski, Vintage News, April 17, 2018

When Ty Cobb was suspended for beating up a heckler during a game with the New York Highlanders (soon to be Yankees) on May 15, 1912, the rest of the team refused to play the next scheduled game. However, the Tiger’s management signed up replacement players so the game went on. The Tigers watched from the stands on May 18 but returned to play the next game.

Sources :

Michigan History, May/June 2011.

“Cobb Not Reinstated; Tigers Quit Field”, Detroit Free Press Sporting Section, May 19, 1912.

For another account, see Baseball’s First Strike, Philly Sport History, May 18, 2011.

On May 15, 1926, the Victoria (B.C.) Cougars hockey team was purchased by a group of Detroit businessmen — led by Detroit Athletic Club President Charlie Hughes — and renamed the Detroit Cougars. This team would go on to become the Detroit Red Wings.

Though the Cougars were based in Detroit, the team had a significant problem: It had nowhere to play. As such, the team’s inaugural season of 1926-1927 was played in Windsor. Meanwhile, on March 8, 1927, the cornerstone for a new hockey palace was laid at the corner of Grand River Avenue and McGraw Street.

Eventually Olympia Stadium was completed and on November 22, 1927, the first National Hockey League game was played in Detroit, when the Cougars faced off against the Ottawa Senators. The ceremonies that took place that night incorporated professional figure skating between periods and performances by the University of Michigan marching band. Michigan had opened its famous football stadium – known today as the “Big House” – in Ann Arbor on Oct. 22, 1927, before 87,000 fans with a 21-0 victory over Ohio State, and wanted to help successfully inaugurate the new Olympia, as well. The band played “America,” “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “The Maple Leaf Forever.” Before the first face-off at the Olympia, Detroit Mayor John W. Smith went to center ice and presented Cougars coach Jack Adams with a huge floral piece.

“Detroit got its first real taste of big league hockey and liked it,” the Detroit Times wrote of the event.

More than 14,000 enthusiastic fans saw one of the most rapid exhibitions in the Olympia last night that it has been their pleasure to witness. The hockey morsel pleased their palates, and they yelled themselves hoarse. It didn’t seem to matter a bit that the Detroit Cougars lost to the Ottawa Senators by the narrow score of 2-1.

It was the spectacle itself that charmed the populace. Fans who have been satisfied with baseball, football and basketball were amazed at the speed of the thing, for hockey is new to Detroit. It is true that local fans who like the ice game have had opportunities to view it across the river, but never before has it been brought right home to them in a big way.

“Hockey, they discovered, is football set to lightning. The athletes flashed around the big expanse of ice like shooting stars, but every electric movement meant something. They squirmed, dodged, ducked, danced and pirouetted on their flashing blades with such rapidity that at times the eye could not quite follow the maneuvers. … That the pastime has caught on here cannot be doubted.”

If Coach Adams’ prideful optimism was at a peak when he rolled into Detroit in the fall of 1927 to take over the coaching duties of the hapless Cougars, it was quickly steamrolled back into proper perspective. Although Olympia was packed with fans on opening night, it soon became apparent that hockey was far from “catching on” in Detroit. Detroiters didn’t know or understand hockey. They thought a cross check and the blue line were tailor’s patterns. Hockey was viewed as a Canadian curiosity, and many of the fans who attended the games came over from Windsor. Couple that with the fact that the Cougars were an awful team, and you got many of the hometown fans rooting for the opposition.

Compounding the indifference of most of the city’s sports fans was the fact that their “hometown” NHL club had played its first season across the Detroit River in Windsor, Ontario. As far as some Detroiters were concerned, that made the Cougars a Canadian team.

“I’ve never seen a place like this in my whole life,” a disillusioned Adams moaned one night after a loss to a visiting Canadian contingent. “There just can’t be another city in the world where the home team isn’t popular. Even when we win, which I admit isn’t too often, we get booed. Things just have to change around here.” The quote is featured in “If They Played Hockey in Heaven: The Jack Adams Story” by Phil Loranger.

On October 29th 1929, a day which will forever be known as “Black Tuesday”, the stock market crashed and money became tight. Gone were the days of Detroiters spending extra cash on entertainment; in were the days of struggling to acquire basic necessities. As the attendance and event bookings began to dwindle, Olympia’s management started to focus more on its signature attraction, hockey. Though the team had been terrible over the course of its first six years, Adams, doing double duty as coach and general manager, had been laying the foundation for a franchise that would carve a niche in the very soul of the city.

First and foremost, it is important to understand that there wasn’t just one hockey team calling Olympia home from 1927-1936, there were two. Having nowhere near the financial backing of other organizations that could afford talented players, Adams was determined to develop his own. With this idea in mind, the Detroit Olympics were born. The idea of having a minor league team was by no means new to sports, or even hockey in particular, but Adams insisted that his minor league team played at Olympia so he could mold his young players into the rugged, precision-style gamers that he adored.

Along with developing young players, hockey teams in the Depression era could rarely afford more than 15 men on a roster, and having a second team on hand with cheap talent readily available to replace injured players was often the difference between success and failure. In the 1930s, the Olympics grew to have its own loyal fan base, and being able to draw 96 games worth of revenue — instead of just the 48 that the Cougars played — helped to carry the stadium through the most uncertain times in its history.

In 1930, the team was renamed the Detroit Falcons. Adams had been doing everything in his power to get the Motor City to embrace hockey, including writing a weekly article for the Detroit Times called Following the Puck. By 1931-1932, three stars (Larry Aurie, Herbie Lewis and Ebenezer “Ebbie” Goodfellow) had emerged from the ranks of the Olympics and would form the core of the franchise, leading the team to a third-place finish, its most successful season up to that point.

However, while things were looking up for the team, the finances of Olympia Stadium were so dire that in 1931-1932, the stadium’s owners had gone bankrupt and Adams was working for the bankers who were managing the organization through receivership. In an era of hockey history in which teams were constantly folding and being relocated, the team’s future would never be more in doubt.

“Things are so bad around here that I’m having to put up my own money sometimes to meet payroll,” a downhearted Adams confessed to a friend near the end of the season. “We’ve been riding day coaches all season on the road and eating cold sandwiches, candy bars and oranges when we can afford to buy them from hawkers. I just hope we don’t break any more of our sticks, because we’re at a point where we just can’t afford to buy any new ones,” he groaned. “Last week, a gang of kids over near the stadium stole some of our sticks, and if the police hadn’t recovered them, we’d be kicking the puck with our skates.”

Later, Adams told a gathering of associates that if Howie Morenz, the incomparable center of the Montreal Canadiens and the greatest hockey player of his generation, had been available “for $1.98, we couldn’t afford to buy him.”

It was at this moment, that a savior arrived. James Norris was an immensely wealthy Chicago grain magnate and hockey fanatic who had long dreamed of becoming an NHL owner. Barred from doing so in his hometown by Chicago Black Hawks owner Maj. Frederick McLaughlin, Norris switched his attention to the struggling Detroit franchise and bought Olympia in 1932, along with all of its interests (including the hockey teams) for $100,000, the equivalent of $1.7 million today, when adjusted for inflation.

Retaining Adams and settling the debts for the stadium, Norris decided to change the team’s name again. Having played for an amateur team in his youth called the Montreal Winged Wheelers, Norris thought the logo of a winged wheel would be far more relevant to Detroiters, and in 1932 the Detroit Red Wings were born.

In their first season as the Red Wings (1932-33), the team reached new heights of success, tying the Boston Bruins for first place and winning its first playoff series. In 1933-34, the Wings were even better, winning first place outright and advancing to the Stanley Cup Finals. With this success, Detroiters finally began to embrace their team, but still not at the level that would guarantee the franchise’s future. A spark was needed to truly endear the team to the people of Detroit.

In order to understand the importance of the 1935-36 season, keep in mind that just a few years earlier, in 1933, Detroiters didn’t have much to cheer about. Not only was the city gripped in the throes of the Great Depression, but the Detroit Tigers had finished in fifth place and had been underwhelming the fans for so long, attendance had fallen to its lowest since 1907. Three efforts to establish a professional football team had failed, the last attempt had come in 1928. While the Red Wings had achieved a measure of success, by no means had the team captured the imaginations of the city. In short, Detroit was viewed by the rest of the country as a second-class, Midwest baseball town that had never won a World Series.

In 1934, all of this began to change. Before the 1934 baseball season, Tiger ownership had acquired the greatest catcher of his age, Mickey Cochrane, from the Philadelphia Athletics for the then-extraordinary sum of $100,000 (about $1.7 million today). During spring training, Cochrane made the startling prediction that the Tigers would play in the 1934 World Series — and his prediction would come true. For a city that had been trampled on by the Great Depression, the Tigers’ renaissance drove the city into a baseball fever.

Though the Tigers lost in the seventh game of the 1934 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, the city would soon embark on the greatest season in the history of American sports. The first was the creation of the Detroit Lions, which were brought to the Motor City from Portsmouth, Ohio, amid the Tigers’ euphoric season of 1934.

That year, an unknown Detroit boxer named Joe Louis turned pro, fought and won his first 12 fights (including three fights at Olympia Stadium), positioning himself as the ninth-ranked heavyweight going into 1935. While the Red Wings seemingly took a huge step back after finishing in fourth place, the midseason acquisitions of two young superstars — Syd Howe and Scotty Bowman — would help set the stage at Olympia Stadium.

On Jan. 4, 1935, 16,000 boxing fans in Detroit turned out for a special event. Not for several years had a heavyweight champion fought at Olympia Stadium, and on this night, Max Baer was putting his title on the line against Babe Hunt. But the match that Detroiters would be talking about starred a young unknown local boxer who had won his 13th fight with such skill, people began to talk about him as being a challenger for the heavyweight crown.

“Perhaps it was the contrast of Baer’s clowning, but we left Olympia with the conviction that we had looked upon the best heavyweight prospect in many years of resin-sniffing,” the Detroit Times marveled the following day. “When he finished, [Patsy Perroni’s] gruesomely scarred face was a welter of bruises, and his waist was livid from the terrific body punishment he suffered.

“Louis … boxes beautifully and hits with deadly force. He is quick and well coordinated. He can hit from any angle. He fights methodically but with deadly seriousness and the expression on his face doesn’t change during the fight. He is not a showman, but he is a fighter.”

Before that night at Olympia, boxing had been in decline. Between the Great Depression and the lack of a true superstar, the rise of Joe Louis electrified the boxing world, and as his fights grew in importance in 1935, so did the massive street celebrations that followed. By the end of the year, Louis had become an international superstar and the pride of Detroit.

As incredible as the rise of Louis was, however, there would be many more celebrations. The Tigers would win their first World Series, while the Lions would won their first National Football Championship. On the same day that the Lions won their first title, Dec. 15, 1935, the Red Wings moved into first place and talk of Detroit as the City of Champions began.

The “Tigers are resting atop of baseball’s golden stairs,” the Detroit Times wrote on Dec. 15, 1935, “The sulking, shuffling shadow of Joe Louis stands over the boxing throne. Official coronation ceremonies will take place sometime next summer. The Red Wings are storming through [the] hockey wars with the lusty thump of hard-riding Cossacks. And today, bless their hearts, the Detroit Lions [brought] the professional football championship of the world to this town of Champions.

When Horace Greely said, ‘Go west, young man,’ he probably secretly qualified it by adding: ‘Don’t go too far west, young man. Stop off at Detroit.’ Yes, indeed, it looks as though all the professional sports titles worth owning will come to roost on Detroit’s mantelpiece.”

For the first time in the team’s history, the Red Wings became the darlings of Detroit, and as they fought for their first championship, many people who may have never even thought about hockey were now swept up in the excitement of a team playing its hearts out in pursuit of something more than just a Stanley Cup. As the season progressed, Olympia began to see sold-out crowds that shook the rafters in their enthusiasm.

The Wings “were angry, greedy wolves that ganged the opposition, and skimmed the ice with burning, red hot steel,” the Detroit Times wrote in January 1936. “It all brought Detroit nearer to the ‘grand slam’ in sports. The same indefinable something which rode with the world champion Tigers, the world champion Lions, and the ‘uncrowned’ world champion, Joe Louis, propelled the strong legs and stout hearts of Jack Adams’ Red Wolves. More than 14,000 fans, occupying every seat as well as every available inch of standing room, gazed down on the ice drama being unfurled below.

“Bodies collided as if shot from springs of steel. There were scrambles in front of nets … violent bumpings along the boards … a burst of speed and then the spilled form of an athlete sliding across the white ice on his face. The 14,000 mingled screams and boos.”

The 1935-36 City of Champions season is one of the greatest, albeit unknown, stories in the history of sports, and no team benefited from it as much as the Red Wings. The dogfight that this team went through against some of the greatest players in NHL history was simply extraordinary and the fact the Detroit Olympics won their own championship merely one day after is the stuff that legends are made of. Carrying the hopes of a Depression-weary city on their shoulders to the eventual Champions Day celebration at the Masonic Temple endeared the Red Wings to Detroit. The Wings would repeat as Stanley Cup champions in 1936-37.

The legacy of the Detroit Red Wings was secured and although they no longer play at the Olympia, they still capture the hearts of Detroit hockey fans.

Source: Charles Avison, Olympia Stadium, Historic Detroit web entry.

The White House announced Tuesday afternoon that Charles Kettles would receive the Medal of Honor from President Obama on July 18 for his bravery during the Vietnam War.

Kettles, 86, recalls the events of May 15, 1967: flying his UH-1 helicopter time after time after time into dizzying, withering fire to save the lives of dozens of soldiers ambushed by North Vietnamese troops in the Song Tau Cau river valley; nursing the shot-up, overloaded bird out of harm’s way with the final eight soldiers who’d been mistakenly left behind.

“With complete disregard for his own safety …” the official narrative of that day reads. “Without gunship, artillery, or tactical aircraft support, the enemy concentrated all firepower on his lone aircraft … Without his courageous actions and superior flying skills, the last group of soldiers and his crew would never have made it off the battlefield.”

Kettles, born and bred and retired in Ypsilanti, Mich., remembers how he felt after he touched down nearly 50 years ago for the last time, finally safe. Unrattled and hungry.

“I just walked away from the helicopter believing that’s what war is,” Kettles told USA TODAY. “It probably matched some of the movies I’d seen as a youngster. So be it. Let’s go have dinner.”

On that May morning in Vietnam, Maj. Kettles’ and several other helicopter pilots ferried about 80 soldiers from the 1st Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division to a landing zone near the Song Tra Cau River. The river, just eight or 10 feet above sea level, drifted past a 1,500-foot hill.

“Very steep, which set them up for an ambush,” Kettles recalls. “Which did happen.”

Hundreds of North Vietnamese soldiers, dug into tunnels and bunkers, attacked the Americans with machine guns, mortars and recoilless rifles.

“Two or three hours after they were inserted, they had been mauled over and the battalion commander called for reinforcements,” Kettles says.

Kettles volunteered to fly in reinforcements and to retrieve the wounded and dead. As they swooped in to land, the North Vietnamese focused their fire on the helicopters. Soldiers were killed before they could leap from the aircraft, according to the official account of the fight.

Air Force jets dropped napalm on the machine gun positions overlooking the landing zone, but it had little effect. The attack continued, riddling the helicopters with bullets. Kettles refused to leave, however, until the fresh troops and supplies had been dropped off and the dead and wounded crowded aboard to be flown out.

Kettles ran the gantlet again, bringing more reinforcements amid mortar and machine gun fire that seriously wounded his gunner and tore into his helicopter. The crew from another helicopter reported to Kettles that fuel was pouring from his aircraft. Kettles wobbled back to the base.

“Kettles, by himself, without any guns and any crew, went back by himself,” said Roland Scheck, a crew member who had been injured on Kettles’ first trip to the landing zone that day. “Immediately, all the pilots and copilots in the company decided, ‘This is Medal of Honor material right there.'”

“I don’t know if there’s anyone who’s gotten an Medal of Honor who deserved it more,” he said. “There’s no better candidate as far as I’m concerned.”

At about 6 p.m., the infantry commander radioed for an immediate, emergency evacuation of 44 soldiers, including four from Kettles’ unit whose helicopter was destroyed at the river. Kettles volunteered to lead the flight of six evacuation helicopters, cobbled together from his and another unit.

“Chaotic,” Kettles says. “The troops simply went to the first helicopter available.”

Just one soldier scrambled into his helicopter. Told that all were safe and accounted for, Kettles signaled it was time to return to base.

“The artillery shut down, the gunships went back,” Kettles said. “No reason for them to stay anymore. The Air Force shut down. We climbed out to about 1,400 feet, a 180-degree turn back toward base camp and the hospital.”

That’s when word reached Kettles that eight soldiers had been left behind.

“They had been down in the river bed in a last ditch defensive effort before the helicopters loaded,” Kettles said. “I assured the commander I would go back in and pick them up.”

Kettles took control of the helicopter from the co-pilot and plummeted toward the stranded soldiers.

The North Vietnamese trained all their fire on Kettles. As he landed, a mortar round shattered the windshields and damaged the tail and main rotor blade. The eight soldiers piled on board, raked by rifle and machine-gun fire. Jammed beyond capacity, the helicopter “fishtailed” several times before Kettles took the controls again from his co-pilot. The only way out, Kettles recalls, was to skip along the ground, gaining enough speed to get the helicopter in the air.

“If not we were going to go down the road like a two-and-a-half ton truck with a rotor blade on it,” Kettles says.

After five or six tries, Kettles got off the ground. Just then, a second mortar round slammed into the tail.

“That caused the thing to lurch forward,” he says. “I don’t know if that helped much. I still had a clean panel, that is, the emergency panel. There weren’t any lights.

The helicopter was still doing what it was supposed to do even though it was, I guess, pretty badly (damaged). We got out of there.”

For the full article, see Heroic Huey pilot to receive Medal of Honor five decades later“,

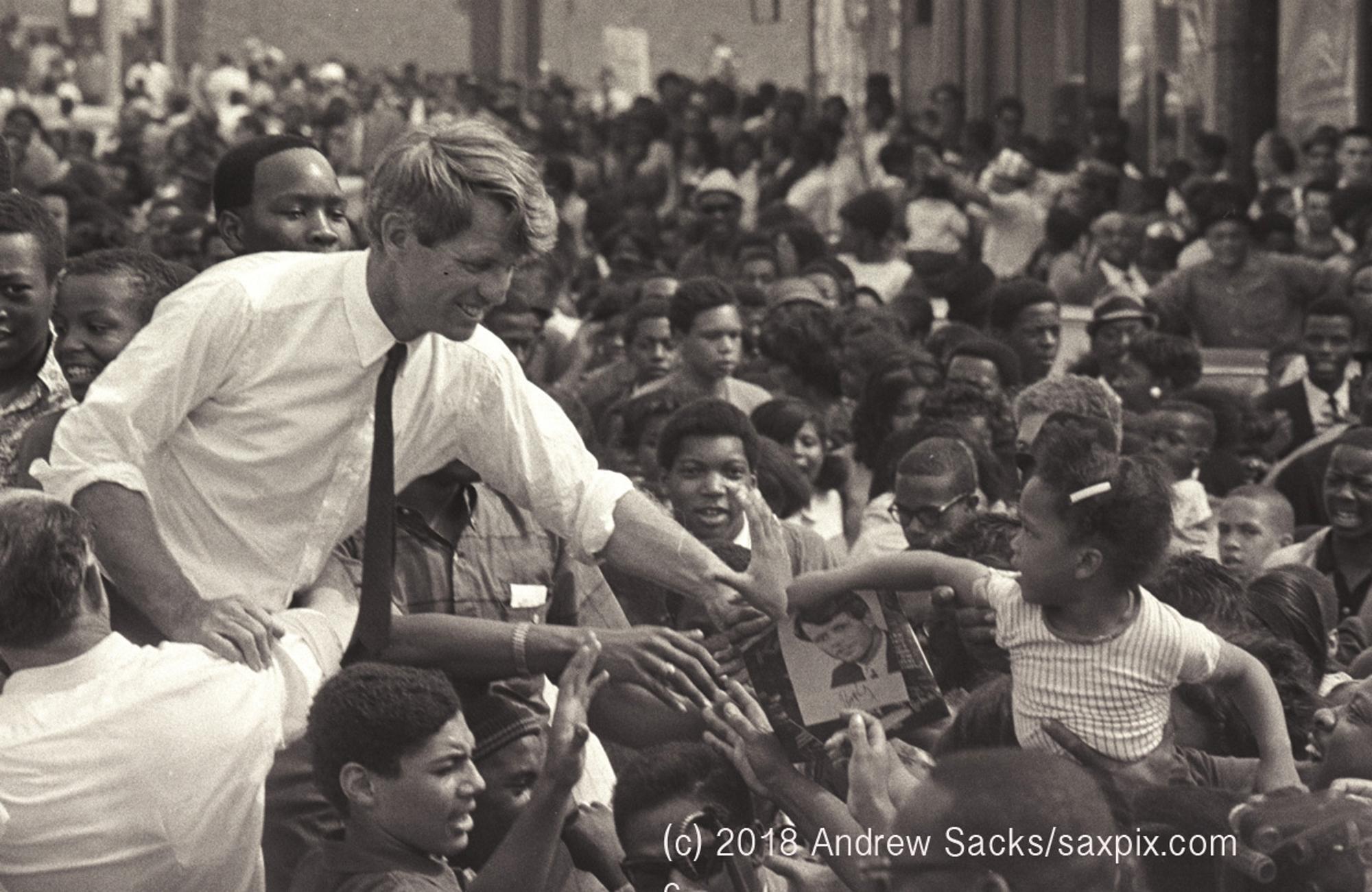

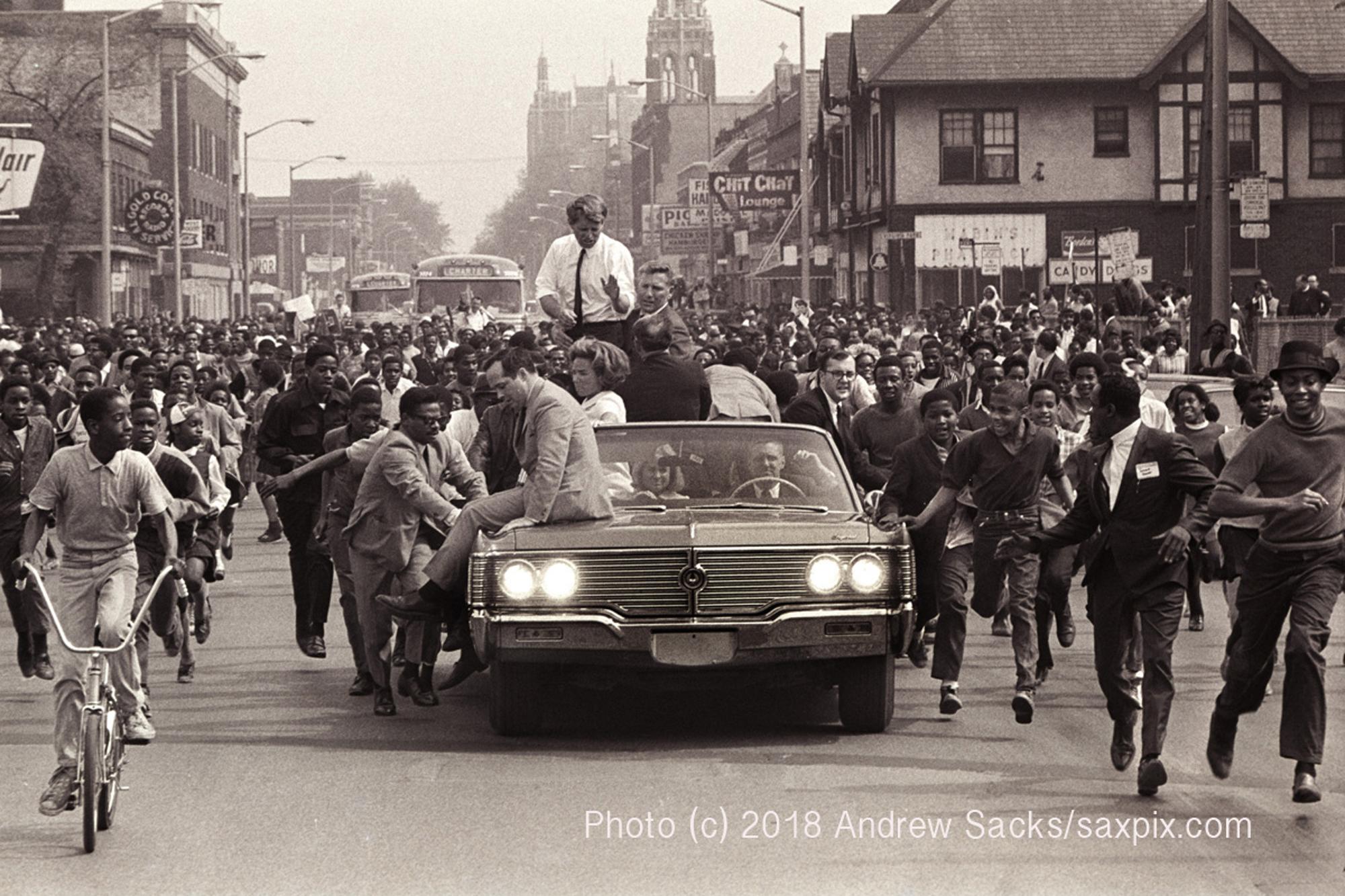

On May 15, 1968, Bobby Kennedy came to Detroit while campaigning for President. He would be assassinated in California on June 5, 1968.

Cheers Amid the Ruins

At a Detroit park on the corner of what was once 12th Street and Clairmount, a photographer glances at the site that sparked three days of violence in 1967.

Back then Andy Sacks was a young journalist for the Michigan Daily student newspaper, one of several who crammed into Robert Kennedy’s motorcade as he campaigned in Detroit in the spring of 1968.

Sacks says after a few stops the motorcade purposely targeted this intersection, an area many at the time said should be avoided because it was seen as one of the most dangerous in Detroit.

“Sure he was a rich guy from Boston. But he seemed to have a vision of government and the way it should interact with the whole of the population of the United States. He connected with inner city people.” – photographer Andy Sacks

Kennedy, however, perched atop an open convertible and was quickly surrounded by an adoring crowd.

“As a photographer I could get pretty close to him,” Sacks remembers. “When he reached down to shake someone’s hand they really gave it a big tug. And I saw him start to lose his balance and begin to fall into the crowd. I just put down my camera and reached out with one of my hands and pulled him back up. He had no bulletproof vest, none of that protection. But he did have someone of his campaign crew holding him around the waist so he wouldn’t be pulled out of the car.”

On the day after Martin Luther King’s assassination in Cleveland, Kennedy gave a speech that was in many ways an indictment of American society, then and now.

“There is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night,” Kennedy said. “This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colors. This is the slow destruction of a child by hunger and schools without books and homes without heat in the winter. This is the breaking of a man’s spirit by denying him the chance to stand as a man and as a father. And this too afflicts us all.”

Kennedy’s words defined what he called the “mindless menace of violence.”

In measured tones Kennedy told the business crowd, “When you teach that those who differ from you threaten your freedom or your job or your home or your family, then you also learn to confront others, not as fellow citizens, but as enemies. But we can perhaps remember that those who live with us are our brothers. That they share with us the same short moment of life, that they seek, as do we, nothing but the chance to live out their lives in purpose and in happiness. Surely this bond of common fate can begin to teach us something.”

On this day in 1976: Mark Fidrych makes his first start with the #Tigers, tossing six no-hit innings vs. the Indians en route to a complete game victory in which he allowed two hits. Fidrych was named the American League Rookie of the Year at the end of the season.

For more information, see Michael Betzold, “When Mark Fidrych made his first start for the Detroit Tigers“, Detroit Athletic Company Blog, April 28, 2016.

Dan Holmes, “35 Years Ago : The Magical Summer of Mark Fidrych“, Detroit Athletic Company Blog, April 23, 2011.

May 16, 1861 : The 1st Michigan Infantry Regiment marched into Washington, D.C., at the start of the Civil War. President Lincolnn, who wondered if the west would support the war, was said to exclaim, “Thank God for Michigan”.

Source : Michigan History, May/June 2018

On May 16, 1891, a riot broke out in Grand Rapids that was finally quelled by fire hoses. The riot stemmed from some 4,000 furniture workers walking off their jobs at 35 plants. Better pay and working conditions were the aims of this workers’ strike that lasted 19 weeks.

Men with weapons, probably professional strike breakers, continued to intimidate the workers and the threat of widespread violence simmered until the riot broke out. Grand Rapids Police Chief Harvey O. CARR, called in “special police” to patrol the factory areas, which ended the violence at the strike sites.

Source: Michigan Every Day

Joe Zainea’s love for people can be felt the moment he shakes your hand as a gracious welcome to the Detroit bowling alley that’s been in his family for more than 70 years.

Zainea, affectionately known as “Papa Joe,” beams with pride as he recalls his father’s purchase of the Garden Bowl on Woodward Avenue in 1946.

“The owner had died and the wife wanted to sell it. My dad came down here and she decided to sell it to him right on the dime,” Zainea said. “Bowling was for everyone; a working-man’s country club.”

The alley was built in 1913, and is on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

“It’s the oldest bowling alley, commercial establishment, in the United States,” Zainea said. “And Detroit is actually the largest bowling population in the United States … I think the bowling registry for metro Detroit at one time was 500,000 bowlers.”

The 16-lane alley is complete with original Brunswick machines, neon lights, DJs and an open-door policy – one that Zainea said helped heal a community during a dark time.

“In the early 60s, we had about 1,500 league bowlers. In the 1967/68 season, we had 300. That was just a month-and-a-half after the rebellion,” Zainea said. “Most people refer to them as a riot, I call them a rebellion.”

Zainea was at Tiger Stadium when he first saw the billows of black smoke rise up into the city’s landscape.

“The announcer said, ‘Please leave the stadium orderly and avoid the Grand River and Northwest area,’” Zainea said.

When he got back to the bowling alley, it was packed with people, mostly business owners who had been ordered by the city to shut down because of a curfew.

“It was traumatic days,” Zainea said. “There was a tank on our parking lot across the street, and the rifles were tri-podded, right on my parking lot.”

The family put out a call for police, firemen, National Guard members and anyone else needing relief to come bowl.

“I’d have neighboring businesses call me up and say, ‘How’s my business?’ And I told them, ‘Why don’t you come down here? You’ve got sons just like my brother and I, let them come down and tend to their business, protect it,’” Zainea said. “They didn’t want to do that. They said it was too dangerous. Well, it wasn’t dangerous here; I can assure you of that.”

As a large portion of the city’s population began migrating out of downtown, Zainea said his family had a decision to make.

“Do we follow our customers and close up? Or do we stay?” he said.

His family stayed and started the Learn to Bowl Plus program to rebuild the bowling population.

The alley offered four weeks of free bowling to anyone who taught bowling classes, with the end goal of turning the learners into league bowlers.

“On the fifth week, if you were one of the teachers and you organized the league, we would end up paying you half of what I took in,” Zainea said. “It really sparked something. By 1970, we had 2,800 bowlers.”

Zainea credits one thing to the longevity of his family’s bowling business.

“They key is that those doors are open to everybody,” he said. “It’s a matter of hospitality, and that’s engrained in our bodies. We don’t just have them bowl, take their money and have them leave, we know them. We embrace them.”

Source : Alex Atwell, “Oldest commercial bowling alley in US still going strong in Detroit; Detroit bowling alley was built in 1913“, ClickOnDetroit, May 16, 2017.