State Senator Virgil Smith tendered his letter of resignation three days after the Detroit Democrat began a 10-month jail sentence for shooting up his ex-wife’s car.

The letter of resignation, which will become official when the Senate returns to session on April 12 (2016), was one sentence long: “I resign as Senator of the 4th District.”

Smith’s resignation will become official when his letter is read into the Senate Journal in April.

Smith had been been previously stripped of his committee assignments following his arrest for the domestic violence incident but remained a member of the Senate.

Sources :

George Hunter and Louis Aguilar, “State Sen. Smith held in shooting at car”, Detroit News, May 10, 2015.

Smith resigns from Senate 3 days after going to jail“,

Emily Lawler, “Deaths, drugs and skullduggery: A brief history of Michigan political scandals“, MLive, August 21, 2015; Updated August 24, 2015.

Maserati has announced it is moving its North American headquarters from New Jersey to the former Walter P. Chrysler Museum in Auburn Hills this year so it can be closer to its parent company, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles.

Maserati became affiliated with Chrysler when Fiat acquired a controlling stake in the Auburn Hills automaker in 2009. Despite that affiliation, the Italian luxury brand has operated separately in North America from Chrysler.

Maserati’s global headquarters is in Modena, Italy, and will remain there. The company also has regional headquarters in Dubai, United Arab Emirates and Shanghai, China.

For the full article, see Maserati moving North American headquarters to Auburn Hills“,

Before there was Beaumont Tower or the MSU Union or even the Sparty statue, there was the Rock, a symbol of Spartan spirit.

A gift from the Class of 1873, the Rock is a 18,000-year-old pudding stone — yes pudding stone — that was left behind from a glacier.

The class began excavating the stone, located at the corner of Grand River and Michigan avenues.They dug it up, then relocated it using a team of 20 oxen to haul it north of the MSU Museum near where Beaumont Tower now stands.

Overnight, the stone sank below the surface of the ground. Eventually it was raised and inscribed with the words “Class of ’73” as a memento to the class’ senior year.

During the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, the Rock became known as the “Engagement Rock.” When a guy wanted to propose, he’d take his girlfriend to the Rock and pop the question.

A bench was even added in front of the Rock, and it was said that only engaged or married couples could sit there.

A man and woman are sitting on the bench, in front of “Engagement Rock,” while holding each others hands and foreheads touching, April 21, 1958. (Photo: Courtesy photo/Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections)

he Rock became a political platform and billboard for different groups in the 1960s and 1970s.

Students held rallies and protests at the Rock, where they painted slogans and controversial messages, including obscenities offensive to some of the alumni.

In an attempt to fix this situation, and to keep it safe from more graffiti, the Rock was moved just outside the Department of Public Safety Building in September of 1977.

The move didn’t last long.

Due to complaints and outcry from the students, it was moved back to its original location near Beaumont Tower that same day.

In September of 1985, the Rock was moved to its current location on Farm Lane next to the Auditorium in an attempt to prevent the trees and sidewalks surrounding it from being damaged.

The informal rules for painting the rock go something like this: 1. Anyone can paint it. 2. But they really should paint it only at night. 3. If you’re not standing guard over what you painted, see Rule 1.

One of the most poignant moments in the history of the Rock occurred on the evening of September 11, 2001. Within hours of the September 11, 2001 attacks, virtually every activist group on campus, along with the university administration, had organized an impromtpu candlelight vigil at the floodplain next to the Rock. The Rock was painted green and white with the words “MSU students in remembrance and reflection” on the front, and an American flag on the back. Several thousand students attended. In a break from normal rock-painting etiquette, the university asked all campus groups to abstain from repainting the Rock for one week.

On Wednesday, April 9, 2014, at 9:00 pm, hundreds gathered at the rock to hold a vigil for Lacey Holsworth, dubbed “Princess Lacey”, a young 8-year-old girl, with terminal cancer, who befriended the MSU Basketball team and whose story was a source of inspiration nationwide. The rock was painted white, with “MSU Loves Princess Lacey” on the front, and “Love Like Lacey” on the base. Students then proceeded to sign the rock with a black sharpie, leaving their own personal messages to Lacey, who had passed that morning. Throughout Thursday, dozens of students an hour stopped at the rock, adding their names, leaving flowers, and paying their respects. A movement, highlighted by an article in the Detroit News, sought to ban all future painting of the rock, and to preserve it as a permanent memorial to Lacey. But by April 21, 2014, four days after her memorial, it was repainted with the message “Congratulations graduates, be a hero to someone” [1] marking the longest period, in recent history, that the rock had gone unchanged.

Sources:

“The Rock” – Gift of the Class of 1873

Stefanie Pohl, “New book celebrates tradition of the Rock“, MSU Today, April 12, 2017.

Vickki Dozier, “From the Archives: ‘The Rock’ at Michigan State University“, Lansing State Journal, February 7, 2018.

Western Michigan University has selected Georgetown University dean Edward Montgomery to be its next president, replacing retiring president John Dunn. Montgomery is a labor economist who has had prominent roles in the Clinton and Obama administrations, including serving as Obama’s executive director of the White House Council for Auto Communities & Workers.

Western’s board approved the selection during a special meeting this morning. Dunn is retiring at the end of the school year after a decade at the helm of Western Michigan.

“We were fortunate to have a number of gifted candidates emerge through the search process,” WMU Trustee William Johnston, who led the 22-member Presidential Search Advisory Committee that helped identify Montgomery as the successful finalist, in a press release. “Edward Montgomery’s personal demeanor, commitment to transformational change and extensive academic background resonated with all of us involved in the search and spoke directly to the themes that emerged from our numerous listening sessions with university stakeholders.”

Montgomery has held faculty positions at Carnegie Mellon and Michigan State universities as well as the University of Maryland. He has been at Georgetown since 2010.

For the full article, see David Jesse, “Western Michigan names Georgetown dean as its next president“, Detroit Free Press, April 12, 2017.

On April 13, 1827, the Michigan Territory passed a law requiring all African-American people in Michigan to register at county clerk offices. If they did not meet requirements for residency, they were required to leave the territory.

The law was formally known as “An Act to Regulate Blacks and Mulattoes, and to Punish the Kidnapping of Such Persons” and claimed to offer protections to black residents against being apprehended and kidnapped as runaway slaves. Under the law, black people were guaranteed access to the court if that were to happen.

However, the promised protection came at a steep price. Unlike their white neighbors, black residents were forced under the law to register with the county and to provide papers proving their freedom. Within 20 days of moving into Michigan Territory, they were required to pay a $500 bond, to register with the county court and to prove their “good behavior” and means of support. It also made it illegal for anyone, black or white, to help slaves escape to freedom.

It appears that the law was only loosely enforced. There’s only record of one person being prosecuted under it. In October of 1827, a black man in Washtenaw County was banished from the town of Scio for non-compliance.

The following year, the act was amended to create civil penalties for non-enforcement of the law. Even so, many places throughout the Michigan Territory continue to be lax in their enforcement. In Wayne County, Sheriff Thomas Sheldon published a “Notice to Blacks and Mulattoes” that outlined provisions of the law, but it continued to be largely ignored.

As the Civil War drew closer, and Michigan entered the union as a free state, sentiment against slavery grew. Michigan would play a considerable role in the Underground Railroad that helped thousands of former slaves escape to freedom. Even so, it would take decades more for Michigan laws to reflect the equality of all of its residents.

Source : Official Blog of the Michigan House Democrats, April 13, 2015

On April 13, 1861 — the day after the attack on Fort Sumter — Charles T. Foster becomes the first Lansing resident to sign up to fight for the Union at a rally at the State Capitol. Although Lansing was Michigan’s capital city, it was not then large enough to field its own regiment. Charles and his Lansing comrades made their way to Grand Rapids, where they joined the Third Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Foster would eventually lose his life at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Virginia, on May 29, 1862.

Source : Matt VanAcker and Kerry Chartkoff, “To His Country and His Flag”, Seeking Michigan, April 5, 2011.

Also see Men of the 3rd Michigan Infantry

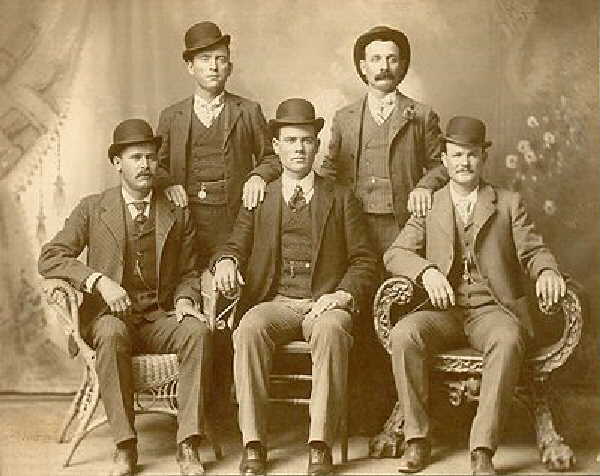

The ‘Wild Bunch’ posed in business dress for this famous photo taken in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1900. ‘Sundance Kid,’ is seated left, front row, Cassidy is at right.

Robert LeRoy Parker (April 13, 1866 – November 7, 1908), better known as Butch Cassidy, was an American train and bank robber and the leader of a gang of criminal outlaws known as the “Wild Bunch” in the Old West.

Parker engaged in criminal activity for more than a decade at the end of the 19th century, but the pressures of being pursued by law enforcement, notably the Pinkerton detective agency, forced him to flee the country. He fled with his accomplice Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, known as the “Sundance Kid”, and Longabaugh’s girlfriend Etta Place. The trio traveled first to Argentina and then to Bolivia, where Parker and Longabaugh are believed to have been killed in a shootout with the Bolivian Army in November 1908; the exact circumstances of their fate continue to be disputed.

Parker’s life and death have been extensively dramatized in film, television, and literature, and he remains one of the most well-known icons of the “Wild West” mythos in modern times.

The Michigan Connection

Anyone who saw the movie “Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid” has those two names engrained in their memories.

Butch and Sundance were two real people, real outlaws, who traveled throughout the country, attempting to avoid the law. One of the states visited by Butch Cassidy happens to be Michigan.

According to the My Bay City website, the story says that after Butch’s gang robbed a train in Wilcox, Wyoming, Butch himself fled across the land to Chicago. From there he went up the eastern coast of Lake Michigan to Frankfort. From there he hit Traverse City and Mancelona, caught a train to Saginaw, and then Bay City.

Still not content to stay still, Butch got aboard a schooner and headed to Harbor Beach (then called Sand Beach) and ended up joining a circus as a wagon driver. Then on to Bad Axe, Cass City, and Pontiac.

Just outside of Pontiac, Butch put on some clothes he took off a scarecrow and began working on a farm. After a week, he figured the authorities had cooled off their search, so he hopped a train to St. Louis, and back to Wyoming – the state where his train robbery took place.

Now, in the Paul Newman/Robert Redford film, Butch and Sundance go to Bolivia, South America. That part is true, but according to the Bay City website, they did NOT die there. After their stay in Bolivia, they came back to the states and Butch once again went to Michigan. While in Michigan, he visited the town of Adrian, where he met and fell in love with Gertrude Livesay. They married in 1908 and moved to Arizona, thus ending Butch Cassidy’s time in Michigan.

The legends of Butch and Sundance continue and their exact endings are open for speculation. Different versions have Butch dying in South America, in the United States, in the northwest, at his old home boyhood cabin, in 1908, in the 1920s, in the 1930s….there is no conclusive evidence where Butch – or Sundance – met their deaths. But we can pretty much take it for granted that Butch did indeed flee the authorities through Michigan.

Sources:

John Robinson, “Butch Cassidy Robs Wyoming Train and Flees to Michigan, 1900“, 99.1 WFMK Blog, December 3, 2020l

The only school to leave and return to the Western Conference/Big Nine/Big Ten Conference is the University of Michigan. Read on to find out why University of Michigan Football Coach Fielding Yost urged Michigan’s Faculty Board in charge of Intercollegiate Athletics to withdraw from the Big Ten in 1907. While the University of Michigan may or may not have withdrawn at this time, the New York Times reported that the University of Michigan was expelled on April 13, 1907 for non-observance or rules, regarding limits on the number of games played each year, the number of years football team members were eligible (3), and possibly limits on the price of football tickets ($.50 at a time Michigan was charging up to $2 and $3).

The University of Michigan pursued its own way for ten years from 1908-1917, picking up new rivals such as Ohio State University, Notre Dame University, and the mighty Michigan Agricultural College (now Michigan State University).

For the full article, see John U. Bacon, “Yost’s walkout”, Michigan Today, June 9, 2010.

Conference Ousts Michigan; Severs Relations With University for Non-Observance of Rules, New York Times, April 14, 1907.

On April 13, 1916, the organization that was to become the Citizens Research Council of Michigan (CRC) began operations in the City of Detroit.

Check out the Citizens Research Council of Michigan Blog.

The Citizens Research Council of Michigan also provides podcasts.

Source : Citizens Research Council of Michigan.

STATE MOVES TO MAN FARMS: Ex-Governor Warner Heads Committee Named to Banish Food Supply Peril. 100,000 WOMEN OFFER TO SERVE AS NEEDED Schools and Manufacturers Will Be Asked to Send Aid to Garner Harvest

Detroit Free Press, April 14, 1917.