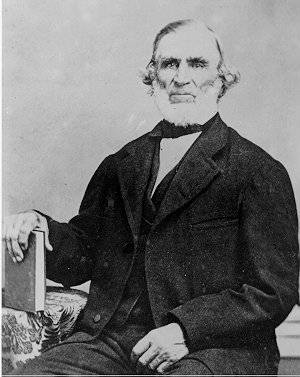

On this day (January 13, 1875), Michigan pioneer Rix Robinson died in Ada, Michigan, where a huge boulder bears testimony to his life.

In Memory of Rix Robinson

Born in Mass, 1792

Founder of West Michigan

Established his Ada Trading Post in 1821 a short distance north on river bank. This table marks the site of his home, into which he moved in 1831.

Explorer of the north-west territory, fur trader, lumberman, lawyer, banker and friend to the Indians, was first supervisor of Kent, now Grand Rapids, state and county commissioner, and state senator. Also helped to revise the constitution in 1850, when he advocated woman suffrage.

The beloved “Uncle Rix” Robinson died in this house Jan. 1875.

Erected by Kent County in 1927.

The stone has been moved at least two times since he died, once in 1970s by the Amway Corporation and again around 2015 i to the Ada Averill Museum grounds to make room for the realignment of Headley Street (urban redevelopment?).

Why is he worthy of note? According to the Historical Records of the Pioneer Society,

At the time that Rix Robinson settled upon the Grand River in the territory of Michigan, there was not a neighbor towards the west (except, possibly, one Indian trader) nearer than the Mississippi River; nor to the north within two hundred miles; nor to the eastward within one hundred and twenty miles. … It was largely through his influence and efforts that the Indians of western Michigan entered into the treaty by which they sold their lands north of the Grand River to the government for a fair compensation; and that they and the White settlers lived together so peaceably that our early history presents none of the bloody scenes that disfigure the early history of Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana; and the further facts of his participation in the early administration of affairs in the government of this state, and his prominence in the ranks of the then dominant Democratic party….

The Rest of the Story

Born in Richmond, Massachusetts on August 28, 1789 (or in 1792 according to the rock marker in the above photograph), Rix Robinson was the second son and third child of Edward Robinson and Eunice Robinson. His father was a blacksmith, although he also farmed a few acres of land. Around the turn of the century (1800) his family moved to the fertile Gennesee country to the town of Scipio now called Venice, in Cayuga County, N.Y. In all his mother raised five sisters and eight brothers.

He received an excellent education for the times at a local common school and an academy in Cayuga County. At the age of about nineteen years, with the approval of his parents, he began the study of law at Auburn, New York, in a law office of excellent repute, which he continued for three years, and then was admitted to practice law in 1811, or possibly in 1812. Before he had a chance to start a law practice, the War of 1812 commenced. His father was a very bitter opponent of it, as were many from Connecticut and Massachusetts who considered it unnecessary and suicidal.

Samuel Phelps, a neighbor living a half mile away, had received appointment as a sutler to some of the troops then massed on the Canadian frontier, and not having enough capital, and needing a bright, energetic, and active assistant, proposed that Robinson go into partnership with him and furnish $1,000, a very large sum of money in those days. His father approved of it as a business venture, and furnished him the money, having to borrow a portion of it. Mr. Phelps stayed principally with the troops, and Rix made the purchases and saw to their transportation to the places needed. While thus engaged, he and his elder brother Edward, were sent draft notices, to help fill up the New York militia regiments. His father’s opposition to the war was so strong that he was determined that neither of his sons should go, and commanded them to keep out of the way of the officers sent to pick up the drafted persons, not a very hard job at that time. Rix was upstairs at the residence of his sister, Mrs. Eunice Church, a few miles away from his father’s house, writing in a back room when the officers came to take him. They were informed that he had not been there. After waiting awhile and he not appearing, they went away without him, and no further effort to get him was made before the close of the war. This was the only cause of his remaining in the west so long, for he had incurred a heavy fine in common with others, and many prosecutions were began in that region to recover, and his was one of the cases which they announced they would prosecute. They went so far as to issue process which, because of his continued absence, they were unable to serve.

He and his partner continued their sutler business after the close of the war. Without receiving its pay their regiment was ordered to Detroit. Nearly all of its members were largely indebted to them and so they followed to receive their dues when pay day finally arrived. It took twenty six days gather their supplies and travel from Buffalo to Detroit. But the expected pay day did not occur . The regiment was ordered on to Fort Mackinac instead. Phelps and Robinson followed on the brig Hunter, arriving there in November 1815. They received the appointment of post sutlers, and remained until the troops were ordered to Green Bay, where they remained during the winter of 1816 and 1817, after which the troops were dispersed in detachments without receiving their back pay. A part of them were ordered to Dubuque and a part back to Mackinac; the partners separated, keeping with the largest detachments. The regiments were eventually mustered out and disbanded without ever receiving their back pay, leaving the sutlers minus their goods and their expenses.

Mr. Robinson was much chagrined over this and was aware there was little point in returning home where a warrant for his arrest awaited, as well as a hefty fine for skipping his military duty. So he decided to pursue the Indian trading business instead, and suggested it to Mr. Phelps, who agreed. Both of them had fully investigated it at Mackinac and Green Bay through curiosity, and were well acquainted with the good and bad qualities of furs, their values and the best modes and places of marketing them. They each selected a place to trade with the Indians, in, I think, Wisconsin, invested their cash and their goods in goods fitted for the Indian market and incurred considerable indebtedness. In the spring they rendezvoused together at Mackinac, disposed of their furs, and paid their debts, and found that Mr. Robinson had done quite handsomely, considering the difficulties that surrounded him, and that Mr. Phelps had lost about an equal amount. This result surprised them, and resulted in a dissolution, Mr. Phelps returning eastward.

John Jacob Astor had become acquainted with Mr. Robinson before this at Mackinac, and had observed him, his personal appearance, and his ways, and had been favorably impressed. At this time Mr. Astor represented the American Fur Company, a New York corporation established to give the Hudson Bay Company a run for the money. At this time he was engaged in having a large number of clerks brought in, principally from Montreal, and distributing them around to the different stations. Those who showed no aptitude for the trade he would weed out and retain the others as apprentices in the trade. As subsequent events show it was also part of his plan to cover the whole country east of the Rocky Mountains, next to the northern boundary, and then secure the services of the independent traders, as employees, and compel the others to seek his employ by putting one of his best men in the neighborhood of each trader, giving him unlimited supplies, with directions to overbid them with the Indians compelling him to either leave because of lack of business or seek his employ.

It occurred to Mr. Astor that Robinson, who was then a large, powerful young man of about 30 years of age, over six feet tall, of splendid physical presence, apparently a courageous person, somewhat acquainted with the Indian language and habits and Indian trading, might succeed as an Indian fur trader, and resist their attempts to drive him way. Acting on this he made an offer to Mr. Robinson to go and stay through the season of 1818 and 1819, for a given sum, and as his own capital was insufficient, Mr. Robinson gladly accepted it. He was fitted out with supplies and transported to the given point by the employees of the company, and then left to remain there without any companion until the employees should return the following June, to take him and the results of his winter’s trading to the grand rendezvous of the American Fur Company at Mackinac.

Robinson’s assigned post was a dreary one; no Indians visited it, although passing often in sight of it on their way to the Hudson Bay company posts. As the winter advanced their hostility toward him increased. It was evident to his mind that hositilities might pursue, and he could hope for no aid from the equally hostile posts of the Hudson Bay Company. It was also becoming very monotonous to him; his only occupations were to hunt, for he was a remarkably fine marksman, and successful hunter, and passionately fond of the sport until but a short time before his death; to study the Indians as they passed by, noticing the least act and inferring its cause; and to read Shakespeare and the very few other books he had. Towards the close of winter he received unexpectedly a white guest; my recollection is that he stated that he was an army officer, who came on some mission among the Indians and there heard of and visited him. He was indeed gladly welcomed, for his presence broke the monotony that was becoming almost insupportable.

At this time, to all appearance, the mission of Mr. Robinson was a failure and would be fruitless. He had made every possible endeavor to secure the trade or even the presence of the Indians in his log house, that his knowledge of Indian character suggested to him as having any possible effect on the boycott that he was suffering. The old chief of the tribe was particularly active in demonstrations, such as brandishing his tomahawk, etc., and took it upon himself to frequently pass very near to the door of the post, on his way to the other traders, indulging in insults and threats, also shaking a package of furs at him, as much as to say, “Don’t you wish I would sell these to you? I am going to take them to the Hudson’s Bay company’s trader and sell them.” Mr. Robinson didn’t seem to notice it, but waited silently, he saw a collision with them, such as his predecessors had encountered. He had made up his mind that there was some way of outwitting the Hudson Bay company’s people with these Indians, for he saw that they were at the bottom of it. He resolved to study the Indian character as thoroughly as he could, to solve the problem. One of the first things that he noticed was, that the bundle, which seemed to be of superb fur, was arranged to display that fact, and each time seemed to be of the same size; it seemed to him also that each time the furs were too fine to be often got, and he soon concluded that it was the same package every time and not an accidental display of temper, but solely a ruse to insult and annoy him, and drive him away.

Before the departure of Robinson’s guest, the chief accompanied by a number of his tribe, entered the log shanty whose threshold they had not before crossed. Mr. Robinson had, as all Indian traders in those days had, some firewater for sale, but this was kept in a strong log addition, whose hewn plank door (fastened together with wooden pins without any iron whatever) was closed and fastened. The chief seated himself upon a heavy three-legged stool, and the following exchange occurred: “Got any whiskey?” “Yes.” “I want some.” Rix, looking around for furs, “Where are your furs, your pelts?” “Haven’t any.” “Well, I keep whiskey to sell, not to give away.” “I help myself when they are not willing to give it freely.” Upon saying this, the chief jumped up, seized the stool and threw it against the door with such force as to break it open and started toward it. He had hardly got three steps before Mr. Robinson struck him under the ear with his fist. He fell senseless into the fireplace where the logs were burning, Robinson putting his foot on the chief’s head. His guest caught his arm saying, “Hold! Robinson! Hold! He has got enough.” Robinson then dragged the body to the door, telling his followers to take him away or he would kill him; they took him away. His guest, fearing revenge, advised him not to go any more into the woods hunting. During the winter Robinson had hunted a good deal, thereby adding to his larder, and the furs, skins and pelts of the company. He thought it over and concluded that the true course for him was to go with his rifle into the woods, where he could see an Indian as quickly as an Indian could see him, and to shoot him down if he showed the least sign of an attempt at revenge. He said that had he seen the Indian in the woods he would probably have shot him down on sight. The next three days he went with his rifle into the woods to hunt, expecting not game but an Indian, and then gave it up. Some four or five days after that, he was sitting near the fire with his rifle over his knees, priming it, when hearing a slight noise he looked up and saw this chief peeping from one side into the door toward him. Robinson arose, walked to the door, the chief not retreating, and said: “You here?” “Yes.” “Come to fight?” “No.” “Want to fight?” “No.” Chief: “You want to fight?” “Yes, if you come to fight, don’t you want to fight?” “No, made fool of myself the other day, want to make all up with you.” “Well, you have concluded to make it up, have you?” “Yes.” “Well, here is a pipe of tobacco.” They sat down together, smoked it and talked the matter over. From that time the chief and his tribe were his fast friends, and the Hudson Bay company got no more furs from that quarter. The chief himself brought him more fur than any other three Indians, as he was a great hunter and trapper. If any of the tribe came around a little full and was boisterous a look from him to the chief resulted in such Indian being seized by the chief and carried outside. This illustrates not only his general knowledge of human nature but his special knowledge of the Indian character.

The business of the post resulted so well that when his furs, skins and peltries were carried into Mackinac, they were received with great surprise. Unfortunately Mr. Astor was away at that moment. Although Astor’s business partner Mr. Stuart sought to keep him in their employ, Mr. Robinson had resolved to be his own master.

His white guest had some acquaintance with the tobacco trade among the Indians as carried on at that time from St. Louis, and had filled Mr. Robinson with a desire to enter into that lucrative trade. Mr. Robinson drew all of his funds out, went to St. Louis and bought a quantity of tobacco and some supplies and went into business again as an independent Indian trader, and pursued it among them during the season of 1819. The profit he made selling tobacco to the Indians increased his capital to a point sufficient to enable him to again start in business on his own account as an Indian trader. In looking around for a location, he decided that a post on the Calumet river, in what is now South Chicago, would be the most desirable and advantageous, so he commenced there in the autumn. His winter’s business was so good that he found himself able to establish another station on the Illinois River, about twenty-five miles from its mouth, in 1820, and also one in Wisconsin, at or near where Milwaukee now stands. In the years 1819 and 1820 St. Louis was the point at which he disposed of his furs, and purchased his goods and supplies. The journey to and from that place in his canoes and barges was long, slow, tedious, had many portages and was very monotonous. But in 1821 his position changed; he was no longer a mere Indian trader, but became a limited partner in the American Fur Company, Ramsey Crooks and Robert Stuart being, so far as I can learn, the only full partners of Mr. Astor therein. Mr. Astor was at Mackinac, and from there sent to Mr. Robinson a request to meet him at Mackinac, and then offered him the chance to go to the Grand, Kalamazoo, and Muskegon rivers, making his headquarters on the Grand. At this time the British government was paying to the Indians of Michigan an annuity (if it may be so termed) and making presents, at a certain time, at Malden, in Canada, thereby keeping their good will, and, to some extent, securing their furs, etc.

Mr. Robinson accepted the offer and at once closed up his post near the mouth of the Illinois river, and came over to the mouth of the Grand River, although prior to that he had taken possession of a pre-existing trading post near the mouth of the So-wan-que-sake (meaning forked stream, that is the Thornapple) river, where it empties into the O-wash-te-nong (Grand) river. The literal meaning of the name is, “far in the interior;” that is literally, “far off land river.” This post was previously run by Madame La Framboise, another famous fur trader who was half French and half Indian. Having run her murdered husband’s fur trading operations for a number of years on her own, surviving in a man’s world, Madame La Framboise decided she was ready for retirement, and so had sold her station with all its supplies to either John Jacob Astor of the American Fur Company directly or to Rix Robinson his agent (the chronology is a little fuzzy), and retired to Mackinac Island. (Use the search box to find more information about La Framboise, an important figure in her own rite.)

Refocusing on the mouth of the Grand River, Robinson selected a lovely site on the bank of the river at a point from which he could readily penetrate into the remote interior parts of the lower peninsula by means of the Grand River and its numerous long tributaries, navigable for the canoe and the Mackinac boats, as his base of operations. He had become so completely weaned from civilized life as to have no desire to return to it. He married according to local Indian customs, Pee-miss-a-quot-o-quay (Flying Cloud Woman), the daughter of the principal chief of the Pere Marquette Indians, in September of 1821, and eventually had one child — the Rev. John Robinson with her. After she died, he married another Indian woman who had been educated in the mission school at Mackinac. Her name was Se-be-quay (River Woman); this ceremony was performed by Rev. Leonard Slater, the Baptist Missionary at Thomas Station. She was a sister of Na-bun-na-ge-zhick (“half day” or “part of the day”) and the granddaughter of Na-nom-ma-daw-ba, the head chief of the Grand River Indians at the mouth. By her he had no children.

His firmness and decision, his absolute fairness of dealing, his knowledge of their character, and his remarkable knowledge of their language, his acquaintance with their traditions, customs and unwritten laws, his truthfulness, and his taking to himself an Indian wife, resulted in giving him a very great influence among the Native American people.

Many stories illustrating these traits are told of him, including the following two or three.

Nim-min-did, a large, powerful, finely built Indian bully well known on the lower Grand River from its mouth to Flat River, who thoroughly hated the white man, in 1823, conspired with some other Indians, having a like hatred, to thrash Mr. Robinson and drive him from the river, through fear. His conduct on two or three occasions when he came to the Ada trading post was such as to satisfy Mr. Robinson that he meant to give him trouble, when a good opportunity arose, so he was particularly guarded in his intercourse with that Indian. On the return of the Indians from one of their great hunts Mr. Robinson was much gratified by their encamping near his post, until he discovered that Nim-min-did was with them and they had a bottle or two of whiskey. He surmised that now his time of trial had come. He went into his storeroom, cleared an open space, and placed an armful of finely cut rather long maple sticks on the fire. In a little time a lot of squaws and young and old Indians crowded in the room, followed by Nim-min-did, who began jostling the other Indians. Robinson stepped forward to Nim-min-did and ordered him to leave; hardly were the words of refusal out of his mouth before Mr. Robinson caught and threw him into the fire, taking him completely by surprise. The squaws shrieked, the old man ejaculated, “Ugh! ugh!” and the young Indians laughed at the discomfited bully, to whom but a moment before they were ready to bow down. Nim-min-did rolled off the fire, howling with pain, and ran to the woods a few rods away. In those few minutes he had lost his standing and became an outcast. Nothing was seen or heard of him for a number of years, when on one occasion, as Mr. Robinson was in his canoe, being paddled along near Battle Point, on the lower Grand River, a tall Indian stood on the Point and beckoned to them to come ashore. On landing, the Indian rushed up to Mr. Robinson with apparent gladness and friendliness — it was Nim-min-did. After a talk with him, in which he stated that he had gone away a good many days journey, and had been a good Indian ever since, they separated, and none of them ever saw or heard of him after that.

A year or two after that his agent at Grand Haven, told him that one of the Indians there, who was large and reputed to be quite strong and ugly, was in the habit of coming into the store room, and without leave to do so, or paying for it, helping himself to whiskey. The next time Mr. Robinson was there he inquired into it. But a day or two elapsed before the Indian came in and, as usual, proceeded to help himself to the whiskey. Mr. Robinson said, “What do you want?” Reply, “Whiskey.” “Well, if you pay for it you can have it.” “I will have it, pay or no pay,” and the Indian started toward the barrel. Mr. Robinson planted a heavy blow between his eyes, knocking him down and then kicking him out. Several days after a young friendly Indian came to him and told him to look out, for this Indian was bad and had just carefully hid a knife in his breech cloth and was coming to talk with him. Soon the Indian came in and wanted him to go out with him and talk it over. The Indian started to go out behind him. Robinson said, “Go ahead.” When they got off one side, Robinson said, “When we talk this over you may get mad, have you got a knife about you?” “Oh, no,” he replied, he had no knife, he would not get mad. Robinson said, “I must search you.” The Indian had so adroitly secreted the knife that Robinson did not discover it, but the young Indian stepped up and pulled it out from his breech cloth behind. The Indian appeared dumbfounded at being detected. Robinson said, “You have brought me out here into the bushes by the river to murder and throw me into the river, have you?” “No, no!” Robinson was enraged, jumped onto him, threw him into the river and held his head underwater; he became insensible, the bubbles gurgled up through the water, he was drowning him. Some squaws seeing them go toward the bushes of the river bank, had surmised the truth and hurried forward, as was their usual way to prevent, if possible, any collision. Just then they got there and begged so hard of Robinson not to kill him, as he might do, under Indian law, that he passed the seemingly lifeless body to them and walked away. They resuscitated him. Robinson did not see him for more than a year, then he came to him and asked his pardon. After a time he entered his employ and was one of his best and most trusted men for many years.

By 1827 Robinson was running a network of no fewer than 20 trading posts from Kalamazoo in the south to Little Traverse Bay in the north, including posts on the Flat River, at Muskegon, and up the Kalamazoo a few miles from its mouth. The principle one however was located at the mouth of the Muskegon River (Grand Haven), where he and his second wife — River Woman — had a store, a warehouse, and a dwelling house with four rooms, although the one he took over from Madame La Framboise near the confluence of the Thornapple and Grand Rivers (Ada) remained a close second.

In 1832, he would return to the Ada area and build a cabin, earning credit as the first white man to live there. Robinson continued his fur trade business at least until 1834 but as an astute businessman, he could not help but notice the decline in fur-bearing animals as well as the decline in demand for fur skins in Europe.

In light of this fact, he resolved to turn his attention to farming and his mercantile and land matters at Grand Haven, and go out of the fur business except what little might come to Ada station. He had now become very wealthy, and was looked up to and highly respected by the few white settlers that had come in within the few preceding years. In 1834 Mr. Astor had sold out the business and property of the American Fur Company to Ramsay Crooks and a party of eastern men. This required the final settling up of the business at all posts and with all special partners; so in 1835, 1836 and 1837, Mr. Robinson settled up the affairs of the different posts in his charge and his accounts with the company, closing out the Kalamazoo post in 1837, the Grand Haven and Ada posts in 1836, and the other minor posts in 1835, to the satisfaction of both the company and himself.

In 1831 the legislative council of the Michigan Territory by an act approved March 2, had set off sixteen of the present twenty-four government townships of Kent County, and established a county by the name of Kent. In 1834 the council organized the whole county as a township to bear the name of Kent, to take effect on the first Monday of April 1834; they had already attached this and other territory to Kalamazoo for judicial purposes, etc., October 1, 1830, and at the first election, held the first Monday of April 1834, Mr. Robinson was elected supervisor of the township of Kent, which had then an area of 576 square miles, and as such attended the sessions of the board of supervisors of Kalamazoo County in the years 1834 and 1835.

The land where the city of Grand Haven now is, was surveyed by the government in 1832, and was opened up to preemption claims. It was here that Mr. Robinson had his post for eleven years, and he preempted the tract on which it was situated, for he had faith that a city would grow up there when the country was settled. Mr. Robert Stuart had the same faith and purchased a half interest in it, and then sent the Rev. William M. Ferry, the father of Ex. U.S. Senator T.W. Ferry, to go there as his agent. The Grand Haven company was organized, composed of Mr. Robinson, owning one half, and Mr. Stuart, with Mr. Ferry and Ferry’s brother-in-law, Capt. N.H. White, owning the other half interest in the land, who platted the land and named it Grand Haven. Mr. Robinson had become the head of the firm (located at Grand Haven in 1835) of Robinson, White & Williams, as he was painfully reminded when he had to pay upwards of $30,000 of its indebtedness out of his own pocket. When settlers started arriving, Robinson was able to assist with their needs for supplies and farming equipment.

Thus we see Mr. Robinson at the time of the foundation of this State, an ex-Indian trader, engaged in making a large, beautiful farm of several hundred acres, a large landholder, the part proprietor of a village, the head of a large mercantile establishment, and the official head of a new township whose destiny to become a rich, thriving, populous country was even then to be foreseen.

Mr. Robinson had as early as 1835 entered with all of his energy into the matter of emigration to western Michigan, and had procured the emigration of six of his brothers, with their families, in all forty-two persons, from Cayuga County, NY, in 1835, coming in one vessel from Detroit, the schooner St. Joseph. They located and became farmers at different points between the mouth of the Grand River and Flat River, one of its tributaries. This was a precursor to a large emigration from that portion of western New York, during the next two years.

Due to his contacts in Washington including Senator Lucious Lyon, the Michigan Territorial Governor, and others, Mr. Robinson was sought out to assist with securing the Treaty of Washington with the Indians in 1836, accompanying them to Washington for that purpose. By that treaty more than one half of the area of the lower peninsula was ceded by the Indians to the general government, for a full, fair consideration. It reserved special tracts to a number of different persons, including 640 acres to the Indian family of Mr. Robinson. The land is now partly covered by the city of Grand Rapids; it was appraised and its value given them, the government keeping the land. According to Mr. Everett, the amount was $23,040 or $3 an acre. By the time Michigan joined the union as a state in 1837, Robinson, who was already a wealthy man, had closed all his trading posts and had moved on in different directions.

In connection with his going to Washington with the Indian chiefs, who declined to go without Mr. Robinson, who went at the solicitation of the government, on its expense, I will note here the following anecdote. He took charge of the transportation of the chiefs who filled two stage coaches full. They stopped at a tavern in the interior of Indiana; he stepped up to the landlord and said, “I want so many good dinners for these Indians.” They were seated and just helped when the stages again drove up and the drivers announced themselves as ready to go and would not wait, as they were carrying U.S. Mail. Mr. Robinson saw no help for it, and counted out the silver at 25 cents a head, the highest price then paid for a meal at a tavern, many charging as low as half that amount. The landlord said, “You must double that sir.” “That is not fair, we have not even had enough to eat, and that is the highest price usually charged for such.” “Fifty cents is my price sir, it is no fault of mine that the stages will not wait, the food was ready.” It was paid.

On their way back when nearing the same place he would not for a whole day let them eat; the chiefs complained of hunger; his only reply was, “tighten your belts.” A short time before arriving at the tavern, he got up beside first one driver and then the other. The chink of silver could have been heard. They arrived there. He ordered as before, adding that his Indians were very hungry. He didn’t seem to recognize the landlord or the place. The landlord smiled, as much to say, I will make another good haul. The food was set before them. Robinson said, “Loosen your belts.” It disappeared in a minute; they called for more, the girls brought it, the landlord rushed distracted to the door, but no stages were driving up, nor were there any signs of any; more food was the call; all that was cooked was brought up, then the cold meats and everything eatable were brought and eaten up; finally their appetites were satisfied, but the famine in that house was awful. Mr. Robinson stepped up to the landlord and counted out one half dollar a head. “That will not pay me one quarter of the cost of the raw material.” “I can’t help it sir; you set your own price when we were here before, and that is it; and look here friend, it would be well not to play tricks on travelers?” “Well, sir, you shan’t go until you pay me my charges.” “Sir, don’t you know that at a word from me, you and every man about here would be killed in ten minutes? It will not look well for you to attack them or attempt to keep them.” The coachmen were called and were quickly on hand. The whole secret of the matter was, Mr. Robinson had penetrated the innkeeper’s secret and overbid him with the drivers.

At the formation of the state he was appointed one of the first board of commissioners of internal improvements — which the state provided with a five million dollar loan for the formation of a grand railroad system, a grand canal system, and a grand system of river improvements, and, for several years gave almost his entire personal attention and services to the performance of its duties.

Col. Andrew T. McReynolds, then (1836 to 1848) a resident of Detroit (which was then virtually Michigan) and, at that time, one of the most prominent of her business men, and a large factor in the politics of the state, describes the standing and the personal appearance of Mr. Robinson thus: “I knew Rix Robinson from 1834, long before he went into the senate. He was a man of good judgment, and quite pleasant, social, and not at all dissipated; his habits were most excellent. His principal associates in Detroit were John Norvall, Lucius Lyon, Tom Sheldon, U.S. Senator Palmer‘s father, Judge Witherell, Judge Wilkins, and such men of standing always. He was a man of imposing form and stature, dressed neatly, always attracted attention on the streets more than any other man in Detroit, by his size, his general appearance, and a certain massiveness of head and face. People stopped as he passed along to look at him. He was a very positive, determined man; it was difficult to move his convictions. He was a man of sterling integrity; his word was as good as his bond.”

An enumeration of the offices he held, not one of which was solicited by him, for the office sought him, will give convincing proof of the esteem in which he was held in the early days of the state. He was township assessor of Ada in 1838, and supervisor of Ada in 1841. When the supervisor system was restored in 1844, he was again appointed supervisor of Ada. He was selected as a commissioner to build a state road from the Ionia county seat to Grand Rapids in 1840. In 1836-7 he was appointed and confirmed by the senate one of the commissioners of internal improvements of the state of Michigan (previously mentioned). He was state senator from the 5th district in the eleventh legislature, and from the 7th district in the twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth legislatures. In 1844-5 he was associate justice of the circuit court for the county of Kent; was one of the commissioners for improvement of the rapids in Grand River in 1840s.

This portion of a hand-drawn map circa 1830 depicts the rapids in the Grand River. In this map, north is on the right.

While a senator, he introduced a bill to give women the right to vote. Elected to serve as a member of the convention that formed Michigan’s state constitution in 1850, he once again lobbied for women’s suffrage but was unsuccessful. Interestingly enough a bill was passed allowing married women the right to control property they owned prior to marriage so perhaps he deserves partial credit. Also interestingly enough, he was selected by the State of Michigan to serve as a member of the Electoral College for the presidential election in 1850.

The nomination to the office of governor of the state, with a certainty of election, was in his power while the democratic party was in the zenith of its power in this state. He declined to allow his name to be used, solely because of the fact that his wife — Se-be-quay (River Woman) — was an Indian (for whom he had the tenderest affection) and would be unable and unwilling to perform the social duties that were then required of the governor’s wife. She was by no means an uneducated woman and was an excellent housekeeper, but not fitted to shine in social life. She would not even use the English language in ordinary conversation, although well acquainted with it. She was proud of her Indian blood and ancestry, and hardly deemed the generality of white blood up to its level.

Mr. Robinson was possessed of cultivated tastes, read a good deal and kept himself well posted on the topics of the day. He was a quiet man, reserved, but not shy; not given to talking much about himself, and was a very careful, conscientious, truthful man in making statements. His insight into human nature was quite extraordinary. He had great love of his home, his family and his kin, and was always the Red man’s friend, to whom they went in difficulty for counsel and advice.

He had a quiet humor, was a good story teller, when with intimate friends; had a very retentive, ready memory, was energetic and sympathetic. He took up the wrongs of the Indians always, and had them redressed, as in the case of the trial and conviction of Miller for the murder, in 1842, of the squaw, Ne-ga. In the detection and arrest of the fugitive, sheriff Hon. T.D. Gilbert won for himself laurels and evinced considerable skill as a detective, as seemingly he had no starting clue.

His kicking Sim Johnson, one of U.S. President James Buchanan‘s trusted political friends, through the streets of Grand Rapids, for not returning 2,000 silver dollars lent him to enable his wildcat bank to make a good show to the bank commissioner who was inspecting its pecuniary condition, was done in midday, in the most public part of the city. Johnson was

nearly as tall and well formed a man as Mr. Robinson. The ridicule it excited drove Johnson away.

Mr. Robinson was always very hospitable and generous, often aided his friends with his name, to such an extent that at the time of his death, although possessing yet a large property, it was found too not very much exceed his liabilities. He became president of the Old Settlers’ Association of Kent, Ionia and Ottawa counties three years before his death and held that position when he died.

He was a man of temperate habits. Until a couple of years before his death, he was not in the habit of attending divine service, save on funeral occasions. The complete reformation that religion had produced upon his son, the Rev. John R. Robinson, in elevating him from a drunken, dissolute half-breed, a source of constant trouble and anxiety to his father, to a sober, grave, considerate, kind son, a good citizen, a humble follower of the cross, an outspoken disciple, a clergyman working with zeal among his race, and one whose private life had become unblemished, caused Rix to turn his attention to religion, and to ask to be baptized. The last two or three years of his life he was a follower of the cross, and had confidence as to his future life beyond this world.

His intellect was strong and clear; it was only the physical body that was worn out and ceased to be the wrap of the soul. Rix Robinson died from consumption on January 13, 1875 when he was 85. His wife — River Woman — who remained his loyal companion for all those years and for whom he passed on the call to be Governor of Michigan — died the following year on April 3, 1876.

Monument in the Ada Cemetery dedicated to the memory of Rix Robinson by the Old Settlers Association, June 30, 1887. Robinson was a very active member of the Association.

Sources:

A Comprehensive Sketch of the Life of Hon. Rix Robinson; A Pioneer of Western Michigan By George H. White of Grand Rapids, Historical Collections of the Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan, Vol XI, 2nd Edition, Lansing, 1908, p. 186.

Fair shake in the wilderness : the life and times of Rix Robinson / by Steve Harrington. Grand Rapids, Mich. : Maritime Press, [2001]

Ada History by the Ada Historical Society

Jan Holst, “Rix Robinson stone gets new home, more exposure“, MLive, August 13, 2015; updated January 20, 2019.