Detroit, April 10-15, 1882

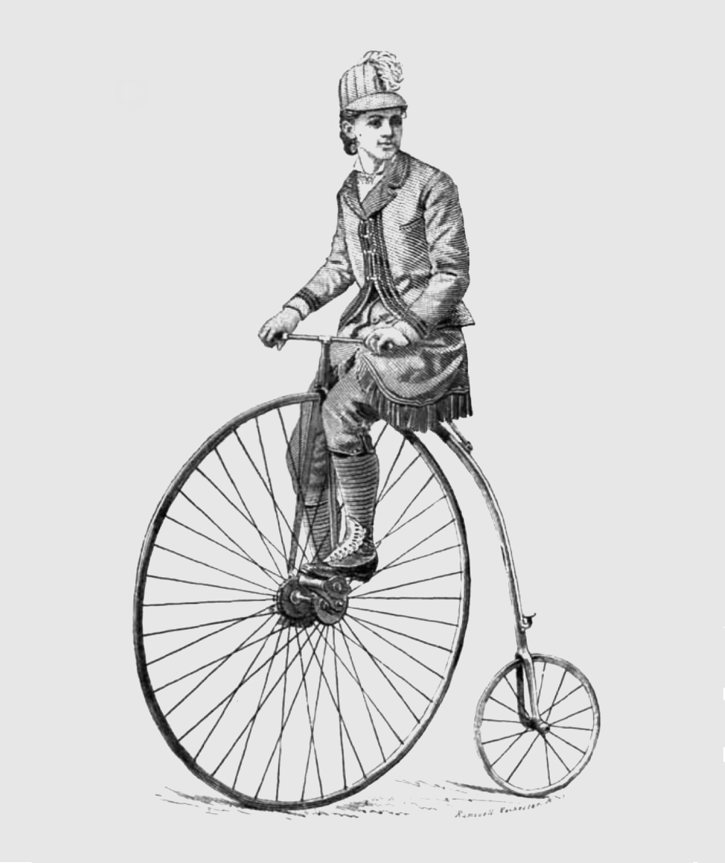

Elsa Von Blumen Aboard a Highwheeler. Sometimes called a “Bone Shaker”, “Velocipede”, “Penny Farthing”, and “Ordinary”.

In the late 1870s women’s bicycle racing was developing into a popular spectator sport. The first exhibitions and/or races were held in France, but soon spread to the United States and then England. Though some denounced the ladies as common showgirls, they were in fact highly trained and motivated athletes. The press covered many of these events and helped make the female riders stars of the cycling world. And the ladies were willing to compete in whatever fashion that guaranteed publicity and/or prize money, whether it be against themselves, male cyclists, pedestrians, or even trotting horses.

In such a vein, Ms. Elsa Von Blumen (a pseudonym for Caroline Kiner) visited Detroit in April 1882 for an exhibition, promising to ride 1,000 miles in six days, something she’d accomplished in Pittsburgh back in December. A custom velodrome (bicycle track) — perhaps the first in Detroit — was built inside the former Music Hall for the occasion.

More About Van Blumen

According to the Auburn Bulletin, Tuesday, February 22, 1887, recycling an article from the Oswego Palladium, “Von Blumen was born in Pensacola, Florida, October 8, 1859 and moved to Albany, N.Y., in the following year. Her maiden name was Carrie Kiner. In 1865 she lived in Oswego. The cold winters, common to all cities upon the great chain of lakes, proved too severe for her delicate frame. She rapidly declined, and was pronounced by several physicians to be in the first stages of consumption. By the advice of friends, she undertook a course in physical exercise, often walking five or six miles a day, together with light exercise with dumb-bells and clubs. The beautiful results were soon manifest. She became possessed of extraordinary powers of endurance, and showed herself capable of undergoing prolonged exertion without injury. About six years ago she moved with her mother and sisters to Rochester, where she has since resided at No.75 Munroe avenue.” For a short time, she was married, but the brief experience did not end happily and she soon returned to bicycle racing as a pursuit.

Von Blumen first made a name for herself as a pedestrian racer, which was also a popular sport at that time. There were plenty of endurance walking races, including six-day races in places like Madison Square Gardens and even Detroit. While endurance racing was challenging, she eventually switched to highwheeler bicycle racing to help support her mother and younger sisters with prize money and appearance fees.

On one such occasion, on May 24, 1881, about 2,500 people gathered at Rochester’s Driving Park to watch the 21-year-old Von Blumen take on a race horse named Hattie R. They cheered as she beat the horse in two out of three heats.

Elsa Von Blumen racing Hattie R from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.

Sue Macy, author of the book “Wheels of Change” says she was “one of the first competitive female athletes in the United States” — a role model for girls and young women at the start of the suffrage movement.

She told Bicycling World in 1881, “I feel I am not only offering the most novel and fascinating entertainment now before the people, but am demonstrating the great need of American young ladies, especially, of physical culture and bodily exercise. Success in life depends as much upon a vigorous and healthy body as upon a clear and active mind.”

Her Detroit Endurance Event

Her visit to Detroit in 1882 didn’t start out well. She contracted a mild form of smallpox (called varioloid) shortly after arriving and was confined to the “pest house.” The case was very light and she soon recovered according to city’s Board of Health report.

To promote her race, images of her were posted at store shops around town. She offered a special invitation to other women.

Her plan was to ride for 91 hours at 11 miles an hour on a track that was 15 laps to a mile. The track was surveyed by the Assistant City Surveyor for accuracy. Chairs were arranged inside the track for spectators. There was a band to play music whenever she rode.

The Free Press downplayed her chances simply based on her appearance, “115 pounds, apparently not possessed of any of the physical characteristics essential to the successful accomplishment.”

She began her Detroit ride on Monday, April 10th, 1882 at 1 AM wearing a steel-gray suit trimmed with bullion fringe. She bowed to the crowd, got on her silver highwheeler bike, and the band started to play. She rode 35 miles in 3 hours before stopping for a two-hour sleep break. At the end of the first day, she’d ridden 140.

She mostly lived out of a Music Hall dressing room, ate three regular meals along with beef tea with crackers and some sips of port wine.

On Tuesday, she rode nearly 60 miles in the morning. Mr. Snow from the Detroit Bicycle Club rode with her for nine miles and crashed “in fine style” per the Free Press. The event manager also offered any local bicyclist $100 if they could match her miles for the final four days. She rode another 100 miles before the day was over.

Wednesday saw a slower pace at just over 10 MPH. Local ride “Robinson” was on the track riding behind her and hoping to win the $100 challenge. She finished the day with just over 449 miles.

Von Blumen continued on Thursday with another 70 miles by 3pm. The Free Press reported her looking “pan and wan, but as determined as ever.” She confidently stated that she would finish, but her nurse did mention her feet were getting cold. They had resorted to using a battery (!) to restore the blood circulation. She ended the day with 583 miles.

Because of the highwheeler’s design, taking a “header” was always a possibility.

Because of the highwheeler’s design, taking a “header” was always a possibility.

Friday’s low moment occurred when a spectator stepped on the track and caused her to crash over the bars. She was thrown up against the steam heaters, hurting her head, and bruising her right leg from hip to ankle. She was carried to her dressing room and everyone thought she was quitting. Not so. She was back on her bike in 30 minutes, dizzy, weak and riding slow. While she ended the day with 707 miles, Robinson was now 7.3 miles ahead of her.

She started riding on Saturday still sore from the previous day’s crash yet got in 46 miles by noon. Her pace quickened. She had 800 miles by her dinner break. Many Detroiters began filling the Hall to watch, but especially women.

At 11:58 PM she got in 850 miles and the crowd burst into enthusiastic applause. As she stopped, so did the orchestra It was an impressive endurance feat, but especially given her illness before the event began.

Robinson did out ride Von Blumen over the four days by just thirteen miles, earning himself the $100 prize.

Financial Troubles

Although the event drew a fair number of paying spectators, it still lost $400. To help pay off her debt, Detroit citizens arranged a benefit race at Recreation Park. Von Blumen would race in a 5-mile time trial event and two 5-mile races against some horses. The Detroit Bicycle Club would also hold races for its members. There was a 25 cents admission.

But before the event took place, her doctor during the 1,000 mile attempt claimed he was owed $121 dollars and the police seized her bicycle.

Fortunately a sympathetic officer let her ride her bicycle and she beat both of the horses before a good number of onlookers.

Another benefit was held a week later where Von Blumen rode a 7.5 miles race against three horse relay team doing 15. She won by a mile, literally.

It appears she departed Detroit for Grand Rapids during the couple weeks that followed and probably stopped at other locations to race as well. In 1886, she rode 367 miles in 51 hours in a race at Rochester’s Convention Hall against a pair of men. They took turns riding, but she beat them without needing a partner. She continued bicycle racing until highwheeler bicycling went out of style.

A sketch of Elsa Von Blumen with her high-wheeler bicycle from 1885 courtesy of the Rochester (NY) Public Library, Local History & Genealogy Division

It doesn’t appear she came back to Detroit, but she certainly left her mark. There’s little doubt her event inspired many Detroit women and girls to take up bicycling, but especially after the safety bicycle became popular in the 1890s.

Elsa von Blumen on a safety bicycle from Wheels of Change by Sue Macy.

Early Detroit Bicycle Shop showing both highwheelers and safety bicycles (Detroit News).

In 1896 Susan B. Anthony noted that “the bicycle has done more for the emancipation of women than anything else in the world.” The bicycle craze helped kill the bustle and the corset, and instituted “common-sense dressing” for women and increased their mobility considerably.

Sources :

Sue Macey, “Elsa Von Blumen & Detroit’s first indoor bicycle track”, m-bike.org , January 26, 2018.

Further Reading: An interesting interview with Elsa Von Blumen about a “very funny incident.” It was published on the front page of the Detroit Free Press on April 28, 1882.

A Vintage Ride entry from the Webster Museum

Caroline Wilhelmina “Elsa Von Blumen” Kiner Roosevelt (1859-1935) entry from Find a Grave.

Mike Fishpool, “Lady Racers: The Origins of Women’s Cycle Racing“, Playing Pasts, June 25, 2018

Wheels of change : how women rode the bicycle to freedom (with a few flat tires along the way) / Sue Macy. Washington, D.C. : National Geographic, [2011] Take a lively look at women’s history from aboard a bicycle, which granted females the freedom of mobility and helped empower women’s liberation. Through vintage photographs, advertisements, cartoons, and songs, Wheels of Change transports young readers to bygone eras to see how women used the bicycle to improve their lives. Witty in tone and scrapbook-like in presentation, the book deftly covers early (and comical) objections, influence on fashion, and impact on social change inspired by the bicycle, which, according to Susan B. Anthony, “has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.”

Bicycle : the history / David V. Herlihy. New Haven : Yale University Press, [2004] During the nineteenth century, the bicycle evoked an exciting new world in which even a poor person could travel afar and at will. But was the “mechanical horse” truly destined to usher in a new era of road travel or would it remain merely a plaything for dandies and schoolboys? In Bicycle: The History (named by Outside magazine as the #1 book on bicycles), David Herlihy recounts the saga of this far-reaching invention and the passions it aroused. The pioneer racer James Moore insisted the bicycle would become “as common as umbrellas.” Mark Twain was more skeptical, enjoining his readers to “get a bicycle. You will not regret it–if you live.” Because we live in an age of cross-country bicycle racing and high-tech mountain bikes, we may overlook the decades of development and ingenuity that transformed the basic concept of human-powered transportation into a marvel of engineering. This lively and engrossing history retraces the extraordinary story of the bicycle–a history of disputed patents, brilliant inventions, and missed opportunities. Herlihy shows us why the bicycle captured the public’s imagination and the myriad ways in which it reshaped our world.