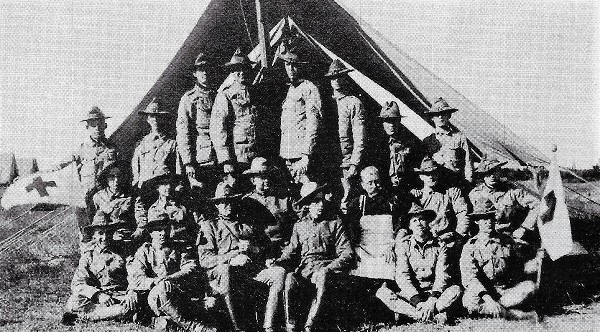

Bay City’s 33rd Regiment established the first Michigan National Guard’s hospital corps during the Spanish-American War, according to Prof. Jeremy Kilar.

Fate intervened 119 years ago and took the life of a sailor from West Bay City along with another local seaman in one of history’s most mysterious naval calamities resulting an unnecessary war that took many American lives.

Seventeen-year-old Elmer Meilstrup of Bay City had hopes of being released from the U.S. Navy, where he was serving as an ordinary seaman aboard the U.S.S. Maine stationed in the harbor of Havana, Cuba on Feb. 15, 1898.

Another seaman from Bay City, Howard Hawkins, also was killed along with Meilstrup when the Maine mysteriously blew up that night.

Meilstrup had written to Congressman Rousseau O. Crump, of Oscoda, hoping for that official’s assistance and expressing regrets for his rashness in running away from home and being tricked by officers who showed him pictures of yachts that they said he would be stationed aboard.

The West Bay City Tribune reported that Meilstrup said: “many young men from the west had been induced to enlist through misrepresentation and had deserted.” But he added: “I will serve on this ship all my life before I will desert.”

The mysterious explosion killed 260 of the 400 sailors aboard. The Maine had been sent to Cuba to protect American interests during a rebellion against Spanish rule.

Another Bay Cityan, William Mattison, was blown from his hammock aboard ship and ended up in the water. But he survived burns and other injuries, was rescued, was treated at San Ambrosito Hospital in Havana, and returned home.

The families of Hawkins and Meilstrup were notified that their “remains were interred at Havana, circumstances being such that they could not be sent home.” However, the Global Burials at Sea Index indicates that Meilstrup’s “cemetery” was Havana Harbor, indicating the body may never have been recovered from the water.

A horrifying account of the situation inside the ship’s hull after the blast was given by Charles Morgan, a trained diver, who went below in a 200-pound diving suit seeking the cause of the blast:

“It was horrible! — As I descended into the death-ship [MAINE’s wreckage] the dead rose up to meet me. They floated toward me with outstretched arms, as if to welcome their shipmate. Their faces, for the most part, were bloated with decay or burned beyond recognition, but here and there the light of my lamp flashed upon a stony face I knew, which when I last saw it had smiled a merry greeting, but now returned my gaze with staring eyes and fallen jaw.

“The dead choked the hatchways and blocked my passage from stateroom to cabin. I had to elbow my way through them, as you do in a crowd. While I examined twisted iron and broken timbers they brushed against my helmet and touched my shoulders with rigid hands as if they sought to tell me the tale of the disaster. I often had to push them aside to make my examinations of the interior of the wreck. I felt like a live man in command of the dead.

“From every part of the ship came sighs and groans. I knew it was the gurgling of the water through the shattered beams and battered sides of the vessel, but it made me shudder; it sounded so much like echoes of that awful February night of death. The water swayed the bodies to and fro, and kept them constantly moving with a hideous semblance of life. Turn which way I would, I was confronted by a corpse.”

That first-hand account was published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine in December 1898, no doubt serving to further inflame the sensibilities of an aggrieved nation.

Diver Morgan had concluded the Maine was blown up by an outside force, primarily because of armor plates he observed were bent upward. “A Naval Court of Inquiry ruled in March that the ship was blown up by a mine, without directly placing the blame on Spain,” History.com reports. “Much of Congress and a majority of the American public expressed little doubt that Spain was responsible and called for a declaration of war.

“Subsequent diplomatic failures to resolve the Maine matter, coupled with United States’ indignation over Spain’s brutal suppression of the Cuban rebellion, and continued losses to American investment, led to the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in April 1898.”

Col. Augustus Gansser, in his monumental 1905 History of Bay County, recalled that Meilstrup, son of J.S. Meilstrup, manager of the Sage (lumber) Company interests, was a graduate of West Bay City High School and a member of the Peninsular Military Company when he joined the Navy in 1897.

Mattison for months suffered for months terribly from burns, wounds and embedded slivers but finally was able to resume his activities.

In 1976, American naval investigators determined that the Maine explosion was likely caused by a fire in its ammunition locker, not by a Spanish mine or sabotage.

The Peninsulars, part of the state military establishment for 24 years previously as Company D, Third Regiment, Michigan State Troops. It included many of Bay City’s most prominent business and professional men on its roster. “When in March 1898 it became certain that war was inevitable, there was a rush of young men to the colors, and hundreds had to be turned away because each company was allowed just 112 men.

A Civil War veteran, J.F. Berdan, was rejected because of his age.

In April the Peninsulars answered the call of President William McKinley for service against Spain. “It was a day never to be forgotten. Thousands thronged the streets, business was suspended, cannons roared, bands played and fireworks added to the din,” recalled Col. Gansser.

Now part of the 33rd Michigan Infantry, the Peninsulars were in rendezvous at the old Bull Run battlefield as they marched through the South. The cheers of people in the former rebel states convinced the Bay Cityans “there was no north, no south, in this war, but a united country had rallied around the old flag.”

From Camp Alger, near Falls Church, Virginia, the men moved to Fortress Monroe and then were transported to Cuba. “War’s horrors were everywhere in evidence here,” Gansser recalled. But thoughts of home came flooding back when one night the Bay City band played “Michigan My Michigan.”

One thousand Michiganders rallied in the trenches with the regulars at San Juan Hill, he recalled. American machine gun and rifle fire drove the enemy back and “the writer witnessed the last desperate charge of the Spaniards on the bloody angle.”

On Sept. 3, “every person living in Bay City was out to welcome the Peninsulars and the 33rd Infantry Band home. “The ranks were thinned (19 had died), many of the boys could hardly be recognized after only four months service, so deep graven were the pieces of evidence of tropical war service under adverse conditions, and many a cheer was hushed at the sight of the wan faces and the emaciated forms.”

Besides battle deaths, the Michigan troops suffered from Yellow Fever and other tropical diseases. A year after the war Michigan emissaries returned to Santiago, looked up the graves under crude wood markers and brought the remains back, some to Arlington National Cemetery and some to Bay City.

Source : Dave Rogers, “Remembering the Maine: Two Bay Cityans Killed Aboard Battleship in 1898; Col. Gansser Recalls Four Months Service of Bay City Troops in Cuba”, MyBayCity.com, February 19, 2018. (Reposted)