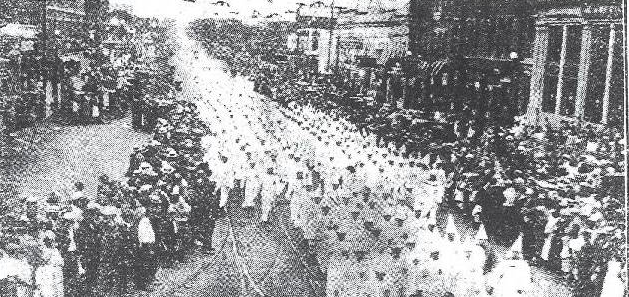

Ku Klux Klan Marching Down Michigan Avenue in Lansing on Sept. 1, 1924.

Ku Klux Klan Marching Down Michigan Avenue in Lansing on Sept. 1, 1924.

Look up the Sept. 1, 1924 Lansing State Journal on microfilm at the downtown main library, and you will see a notice: “Pages Missing.” That day, the Michigan Ku Klux Klan held its biggest “Klonvocation” ever, drawing an estimated 50,000 people to Lansing to watch 15,000 white-robed Klansmen (and women) from all over the state march down Michigan Avenue. David Votta, local history expert at the downtown library, said the pages were torn from the library’s copy and hundreds of others. He’s never seen the front page, but he guesses that somebody didn’t like a picture of Ingham County Kleagle Lawrence H. Nichols getting a new REO sedan — perhaps minions of R. E. Olds himself, staving off a P.R. disaster. The next day’s coverage of the parade in the LSJ is shockingly anodyne. “Colorful parade here is seen by thousands,” reads the jumpline.

The parade started at 2 p.m., headed west on Michigan Avenue and took an hour to pass in review “before huge crowds.” Judge Charles J. Orbinson of Indianapolis gave a speech, urging Americans not to let the country become “a dumping ground for other nations.” The other speakers were designated by Klan numbers, not by name. Among the floats was a huge birthday cake honoring the first birthday of the Women’s KKK of Michigan. At the height of the festivities, a small airplane buzzed Michigan Avenue with a big flaming cross. The Klan was particularly active in the Lansing area that year, going so far as to circulate a petition opposing Michigan State College’s football game with (Catholic) Notre Dame.

Source : Lawrence Cosentino, Lansing’s Parades, Lansing City Pulse, May 13, 2009.

Source : The Times Herald, September 2, 1924.

For more information, see Craig Fox, Everyday Klansfolk: White Protestant Life and the KKK in 1920s Michigan, Michigan State University Press, 2011. Although the picture of the Ku Klux Klan as a small, fanatical organization bent on racial violence and based primarily in the American South is certainly accurate in terms of the organization’s history during the 1860s and the 1960s, according to Fox (PhD, history, U. of York), there was another Klan that existed all over the United States in the 1920s which relied more upon “wide-ranging popular appeals to Protestant morality, prohibition, and law enforcement, rather than overt reliance upon vigilantism.” This “second” Klan achieved a membership of millions by the middle of the decade and spread all across the United States, including to rural Newaygo County, Michigan, where a previously unknown cache of organizational documents and paraphernalia of the 1920s Klan was discovered in 1992, providing an unprecedented opportunity for a case study of the organizational life of “Newaygo County Klan No. 29” from its inception in the summer of 1923, through its 1925 peak, official chartering, and subsequent decline, presented here and placed in its regional context.

Ku Klux Klan Collection available in the MSU Main Library Special Collections unit.

The popularity of the Klan in mid-Michigan reflected fear less of blacks and Jews than Catholics. One man, named Fred, who lived in North Lansing recalled, ‘We lived in a nest of them [Klan members].” Fred’s father was opposed to the Klan and Fred remembered his father being threatened by his neighbors, “They’ll get you. You’ll join.” Against his father’s wishes, Fred witnessed a number of Klan events in and around the city, including the cross burning at the Labor Day rally. As Fred recollected, “the order of priority was first the Catholics, because the Klan feared the Pope was trying to take over the country; second were the Jews. . . then the blacks.”

From Lisa Fine, The Story of Reo Joe: Work, Kin, and Community in Autotown, U. S. A. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004): 67. People’s History of Old Town, Lansing, Michigan