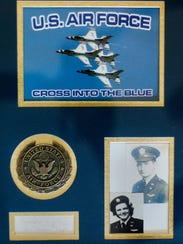

Mildred (Jane) Baessler in the pilot’ seat.

Jane Doyle held a heavy bronze medal in her creased hands, running her fingers over the engraved surface.

It shone in the light streaming through the window of her apartment in a Grand Rapids senior living complex. The words: “The first women in history to fly American Military Aircraft” were etched on the outer rim.

Doyle, 96, smiled slyly.

She earned it — even if it did take 66 years to get the Congressional Gold Medal. It’s the highest honor that can be awarded to a civilian, and Doyle got it for her service during World War II for flying in the Women Airforce Service Pilots program, known as WASP.

It took an Act of Congress to give the medals to Doyle and the 1,073 other WASP fly girls who boosted the war effort. The women were recruited to fly stateside for the U.S. Army Air Forces during the war, freeing up male pilots to serve in combat overseas.

Doyle is the last living WASP in Michigan, according to Texas Woman’s University, the repository for the history of the group. In all, just 69 remain nationally.

She was a trailblazer unafraid to be the first girl or woman to do just about anything — practically a poster child for today’s feminist mantra: nevertheless, she persisted.

“The Women’s Airforce Service Pilots were groundbreaking in the same way that the iconic Rosie the Riveters were — one in flying and one in building the aircraft,” said Kristen Wildes, director of the Ada Historical Society, which with the Cascade Historical Society, featured Doyle as a speaker at a joint veterans event last week.

“When the men left to serve in the war, these remarkable women stepped in to assist in the war effort and get the jobs done. Through their dedication and service, the WASPs got a foot in the door of a future that would slowly open to women in aviation.”

Doyle said she was the first girl in the marching band at South High School in Grand Rapids, playing the French horn. The band director told her: “You can be in it, but you can’t wear pants. You have to wear a skirt.”

“I think I was a problem child because I was always trying something,” said Doyle, who was born Mildred Jane Baessler in October of 1921. She was the youngest of four children.

“I don’t know why my folks named me Mildred,” she says, chuckling. “They never called me that. They always called me Jane.”

Her father, a German immigrant, worked for the Pere Marquette Railway. It was her mother, Emma Baessler, who took her to see the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh when he came to Grand Rapids in August 1927.

She recalled hearing Lindbergh speak in the outdoor amphitheater at John Ball Park. Doyle was just 6.

“It was a big thing over there. The newspapers gave him a lot of publicity when he came, and my mother was just interested in what was going on. … Then, Wrong Way Corrigan came, too,” Doyle said, “and she took me to that.”

Douglas Corrigan was given the “Wrong Way” moniker when he flew across the Atlantic rather than across the U.S. in what many dubbed an intentional mistake after his plans to fly over the ocean were denied.

“And then, when my brother was in high school, he had a music instructor who was a pilot. He took him up for a ride, and I heard him telling about it. But I had never been in a plane.”

It wasn’t until she enrolled in what was then Grand Rapids Junior College in 1939 that Doyle considered flying an airplane was something she could do.

“I was taking engineering drawing and I was the only girl in the class,” Doyle said. ” I was ordered to sit in the back in the corner and the instructor came in and was talking to the fellas about this Civilian Pilot Training Program.

“After the class, I went up and said, ‘How about women? Can I get in?’ And he said, ‘Well, I’ll find out.’ And then he told me that one woman could get in for every 10 men.

“Men had to be 5-foot-4, but women could be 5-foot-2½. So I stretched, and passed the physical and got into the program that summer.”

She did 70 hours of ground school training, and went on to do 35 hours of flying at Kent County Airport at a time when much of the world was at war. She said most Americans understood why President Franklin D. Roosevelt started programs like the Civil Pilot Training Program to ready the nation for its likely entry into the war.

By the fall of 1940, Doyle was enrolled at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and flying with the Civil Air Patrol to keep her pilot’s license.

“I flew with anybody that would take me,” she said.

Then, Pearl Harbor was attacked. Doyle’s brother, Fredrick Baessler, enlisted in the navy as an officer, serving on a destroyer in the Pacific. Her sister joined the American Red Cross.

And one day, a telegram arrived.

It was from Jacqueline Cochran, the founder of a flying program that was recruiting female pilots from around the country to join the war effort.

“I got a telegram asking, ‘was I interested?’ … I responded that I was interested.

And then I got a notice that said … I had to go pass a physical at Selfridge Field,” Doyle said.

“So I had to get a ride over to Selfridge and pass the physical. And then I waited and then I got a notice that I was accepted and could I start the first of November 1943.”

She passed the tests and made her way to Texas for seven months of training at Avenger Field in the town of Sweetwater. Cochrane was insistent that her pilots would be trained to fly every aircraft in service.

Altogether, Doyle and the other WASPs flew 60,000,000 miles of operation flights from 1942-44 and piloted 78 types of aircraft, according to Kimberly Johnson, the director of special collections at Texas Woman’s University.

“The WASP pilots flew every type of plane the men flew, in every type of assignment and mission except for combat,” said Keith Gill, director of exhibits and museum programming at the Air Zoo in Portage.

“When the B26 Marauder bomber and the B29 Superfortress bombers were first test flown they were considered unsafe. It took WASP pilots to fly them in demonstration flights to prove that after modifications had taken place, and male pilots retrained, that the planes could be trusted and were indeed safe to fly. In fact the B26 went on to have the lowest loss rate of any USAAF bomber.

“But it took women pilots flying it to help convince others that it was safe to fly. WASPs also flew top secret transport for the atomic bomb project, towing targets for live-fire aerial gunners and for anti-aircraft gunners on the ground, and countless test flights for equipment.”

Cadets from the Class 44-W-4, from top left, Dorothy Allen, Mildred (Jane) Baessler, and Odean Bishop, from bottom left, Ina Barley and Stella Jo Baker at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas.

They also worked as instructors, and ferried planes from factories to bases. The women took part in engineering and safety tests, along with demonstrations, administrative flights, tracking and searchlight missions and more.

Because they weren’t considered part of the military at the time — they were civilians, the WASPs had to buy their own uniforms, cover the costs of traveling to the training center, and to their assigned bases. They had to pay rent, and cover other expenses. And when a woman died on the job — as 38 of them did — her family got nothing.

“For those that were lost, whose lives were given during the war, the government didn’t pay to get them back home, for their families to lay them to rest. There was a lot of sacrifice, but they did so willingly,” Johnson said.

“What they did was open so many doors.”

When Nancy Parrish learned about the work her mother, Odean Bishop Parrish, and fellow WASPs did during the war, she started a website called wingsacrossamerica.org to honor them and chronicle WASP history. Over the years, she has interviewed hundreds of women who flew for the group.

“Jane is probably one of the most fearless of the WASPs still alive,” said Nancy Parrish, whose mother was better known as Deanie, and was one of the women who roomed with Doyle during training in Texas in 1943 and 1944. “Jane will climb in anything that flies. I love that. It makes you go back in time and think, she must have been very spunky as a child.

“I’m not sure if any of them thought what they were doing was courageous,” said Parrish, who lives in Waco, Texas. “They just wanted to do something to help their country. And every WASP I interviewed loved to fly, and to have something you love in service to your country was a win-win. The timing was perfect because we needed them.”

But then, suddenly, America didn’t need them anymore.

Mildred (Jane) Doyle, 96, a member of the Women Airforce Service Pilots during World War II, met her husband Donald Doyle while working at Freeman Field in Seymour, Ind. Donald, a Lt. Col. also flew planes in World War II.

For the full article, see Kristen Jordan Shamus, “Michigan’s last surviving WWII fly girl recalls her time in the sky, blazing new paths“,